AI is Coming to an Exam Room Near You

Ambient listening interprets conversations in real-time to update electronic health records — and help physicians reconnect with their patients.

Matthew Harris Dec 16, 2024

IF YOU'VE EVER pulled out an iPhone to ask Siri for help with directions, you've dabbled with the same technology that’s poised to change medicine.

For years, we've asked voice assistants to help us find directions, shop and even turn on the lights in our homes. Now, ambient listening — the technology underpinning those functions — might help physicians streamline the tasks that come with maintaining an electronic health record (EHR). In the process, they’ll be able to shift their focus from a computer screen to the patient in the room.

Essentially a virtual scribe, the technology records the doctor-patient interaction and uploads the audio to a cloud server, where artificial intelligence automates transcription. Next, a large language model — think ChatGPT — parses the conversation and drafts a classic SOAP note, which is inserted into the EHR.

Over the past five years, vendors and start-ups have raced to develop tools that can work seamlessly with EHR software. Meanwhile, health systems associated with Yale, Emory, Stanford, Michigan and Pittsburgh have integrated the technology.

By early 2025, Indiana University Health will be among them.

This fall, the state's largest health network was winding down a pilot project testing two systems. Beta testing is underway in 23 communities and is heavily concentrated in primary care specialties. Yet, the tally of providers remains relatively modest.

"There are a couple of places that have a couple thousand physicians using it," said Jason Schaffer, MD, IU Health's chief medical information officer, an emergency medicine physician, and an associate professor of clinical emergency medicine. "We have a couple hundred."

One tool, from an established company in the field, merges automated transcription with Microsoft's generative AI to pick up contextual clues and draft a note for a chart. Using it is straightforward. Once a physician obtains patient consent, they open an app on their phone, press record and upload the audio when the visit ends. Soon, they receive an e-mail with the document attached.

The other vendor is a smaller, emerging start-up "catching up really, really quick," Schaffer said. The company touts that its product can sift a chart to pull in relevant clinical information, incorporate live data, and fold in a treatment plan.

"They've got a deeper integration with our EHR," Schaffer said. "It'll generate a full note, send it to you, and let you edit it. As integrations get better, it will become more seamless."

Rolling out the technology in family medicine, internal medicine, emergency medicine, cardiology and pediatrics was intentional. Conversations unfolding in those settings tend to be broad-based and not as medically complex. IU Health has left it to physicians to decide whether to take part.

"There are clusters of people where they're all in," he said. "But it's not to the point where we can say this clinic is all in and this one isn't. It's pockets of providers who have found benefits."

For now, ambient listening is not being introduced to medical residents, Schaffer said. That may come after seasoned physicians gain more experience with it and its impacts are evaluated. But that decision must be weighed against potential distractions from the objectives of a learner gaining experience and essential medical knowledge.

Tools like these aren't plug-and-play. There's some handholding. For example, a physician might provide a play-by-play of an exam. "You're speaking out loud as you're seeing a patient, such as, 'I am palpitating the abdomen, and there is no tenderness,'" Schaffer said. What might seem like a drawback can be a benefit: It can start a conversation that elicits more detail from a patient and producing a more thorough record.

Schaffer said this engagement has been a byproduct physicians enjoy. As for the accuracy of the notes produced by these new products, feedback was mixed. To a certain degree, those views reflect the physician's personality.

"Some providers are going to be fine with whatever it spits out," Schaffer said. "Others are very, very obsessive about the accuracy and specificity of their notes."

Moving forward, the technology could tackle more complex needs. In many ways, the EHR is just a filing cabinet, and physicians try to find the most efficient ways to extract what they need.

Ideally, Schaffer noted, the technology will evolve to a point where it is rifling through digital drawers and folders to present essential information.

"Do that, and it's a great service," Schaffer said. "Give me a summary of the patient and a longitudinal history of their problem. And I don't want paragraphs or prose. Give me bullet points. Skimming is your friend."

Ordering diagnostic tests, drugs, and prescription management might be trickier. A physician can set preferences in an EHR to make their most common requests with a mouse click. Speaking them out loud in a complex sentence might seem more effortless. But what if AI misinterprets the order?

"It could change the risk factor significantly," Schaffer noted.

Glossary Terms

Training Data: An initial set of data with examples selected and organized by researchers to teach machine learning software to uncover patterns or fulfill some function.

Predictive AI: Think of this as the first generation of AI software. It was developed and deployed to collect and analyze existing data to predict future outcomes.

Machine Learning: An AI approach in which machines learn from data and steadily improve at performing tasks. Over time, the machine independently makes decisions or predictions based on patterns it learned from the data.

Unlocking the Power of AI

IU School of Medicine embraces a powerful new tool to speed research and treat patients.

How Radiology is Becoming a Leader in Adopting AI

Few clinical areas have adopted AI tools faster than radiology, easing workloads and helping overcome a shortage of clinicians.

AI That Learns Without Borders

Decentralized approaches to AI make it easier for scientists to share data, protect sensitive data and develop tools that reflect the diversity of patients.

"We're on the Precipice"

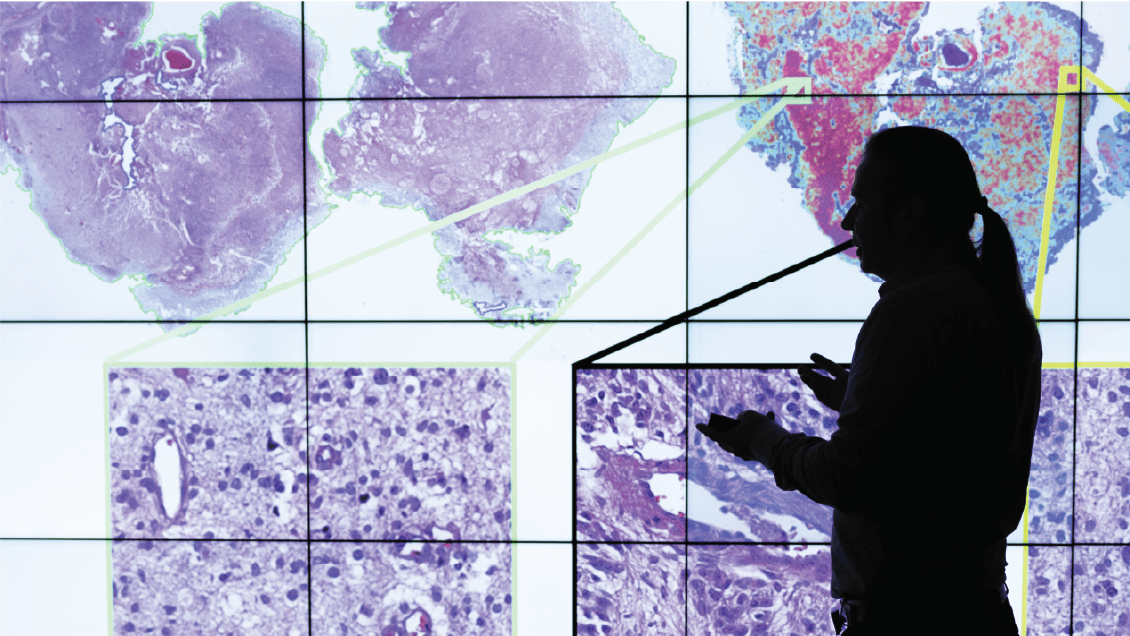

AI powers tools that help pathologists spend less time counting cells and use their refined skills to make complicated diagnoses.

Skin in the Game

An IU researcher’s AI tool shows promise in predicting whether melanoma will return.

Finding a Signal in Noise

Machine learning enables cancer researchers to sift reams of genetic data and identify a protein potentially powering multiple myeloma.

Reducing Bias in AI

In a technology hungry for data, how do we ensure it consumes good information and builds models that benefit every patient?