When it comes to lung cancer, being Black—particularly a Black male—means increased risk. Francesca Duncan, MD, MS, is determined to end disparities in the diagnosis and treatment of lung cancer—the leading cause of cancer deaths in the United States.

“Black individuals have the highest incidence rates and mortality rates compared to any other race,” said Duncan, assistant professor of pulmonary medicine at Indiana University School of Medicine and an associate member of the Indiana University Melvin and Bren Simon Comprehensive Cancer Center.

While 15-20% of people who develop lung cancer are not smokers, in the majority of cases, smoking is linked. Curiously, research shows that smokers in the Black population tend to smoke less over time than their white counterparts yet still have worse outcomes.

“That’s what I found really interesting,” Duncan said. “That’s what started my quest to learn more about the disparities in lung cancer.”

Her initial interest in cancer research began in during graduate school where she studied cervical cancer. Later, she received an intramural research training award where she conducted breast cancer research at the National Institutes of Health/National Cancer Institute working with a physician scientist who studied tissue samples collected directly from patients.

“I thought it was remarkable that you can go from bedside to bench and back to bedside like that,” said Duncan, who would return to this lab each summer during her medical school training at Meharry Medical College, a historically Black medical school in Nashville, Tennessee. “When I began my fellowship training in pulmonary and critical care at IU School of Medicine, I was interested in finding a way that I could merge my interests in cancer research and health disparities.”

“I thought it was remarkable that you can go from bedside to bench and back to bedside like that,” said Duncan, who would return to this lab each summer during her medical school training at Meharry Medical College, a historically Black medical school in Nashville, Tennessee. “When I began my fellowship training in pulmonary and critical care at IU School of Medicine, I was interested in finding a way that I could merge my interests in cancer research and health disparities.”

As she developed her research niche, Duncan found a valuable mentor in Catherine Sears, MD, an extensively published physician-scientist with a focus on lung cancer. Sears’ lab at IU studies the impact of DNA damage in smoking-related lung cancers and potential therapeutic targets to repair that damage and prevent progression.

“I was thrilled when Dr. Duncan approached me during her fellowship training with an interest in studying racial disparities in lung cancer outcomes and in lung cancer screening,” Sears said. “Now a junior faculty, she is leading a team to discover the root causes for these inequities and determine if interventions within lung cancer screening programs can mitigate their impact on those traditionally underserved in medicine.”

Along with pulmonary medicine colleague Edwin Jackson, DO, MBA, Duncan secured a grant from the federally funded Primary Care Reaffirmation for Indiana Medical Education (PRIME) program designed to improve lung cancer screening through a provider educational curriculum and patient educational outreach, in hopes of increasing shared decision making surrounding lung cancer screening among patients and providers.

“Lung cancer screening only became available about 10 years ago, so it’s very new,” Duncan explained. “Less than 6% of eligible people get screening, and even less among Black individuals who carry the burden of this disease.”

Current guidelines, updated in 2021 to help screen more Black patients who tend to be younger and lighter smokers, call for screening of people ages 50-80 who have a “20-pack year smoking history” (people who smoked one pack/day for 20 years, 2 packs/day for 10 years or the equivalent) and who currently smoke or have stopped smoking within the last 15 years.

Duncan is now conducting a pilot program to educate both primary care providers and patients on the process of lung cancer screening.

“Studies have shown that if it’s your doctor talking to you about screening, you’re more likely to agree to it and follow through,” she said.

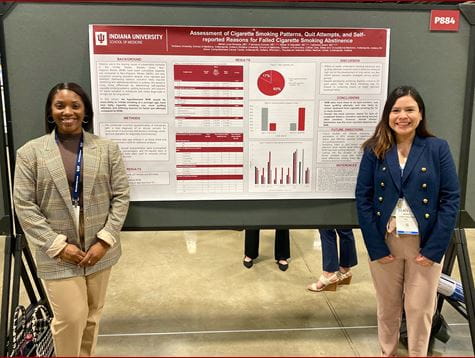

Duncan recently broadened the impact of her disparities research to include the Hispanic/Latinx community via the work of an enthusiastic learner. Mariel Luna Hinojosa, MD, a third-year resident in internal medicine, is working on patient education in the Spanish language.

For Luna, it’s personal.

“My grandpa died from lung cancer,” she said. “I don’t think anybody every brought up lung cancer screening for him. His cancer was metastatic by the time he was diagnosed.”

According to the American Lung Association’s State of Lung Cancer 2022, Black Americans and Latinx Americans with lung cancer are 15% less likely to be diagnosed early compared to white Americans. Both groups are also more likely to not receive any treatment for lung cancer and are substantially less likely to survive five years compared to white Americans.

“I want to identify all the barriers—socioeconomic factors, patient-doctor relationships and the language barrier—to understand why Latinos are less likely to be screened for lung cancer,” Luna said.

“I want to identify all the barriers—socioeconomic factors, patient-doctor relationships and the language barrier—to understand why Latinos are less likely to be screened for lung cancer,” Luna said.

Doing research with Duncan means Luna can be part of systemic change to help more people avoid the suffering of lung cancer.

“Before I met Dr. Duncan, I knew I wanted to be a doctor that helps patients overcome health disparities, but I didn’t know I could do this at a larger scale and try to correct issues within the medical system to make big changes for a population,” Luna said.

Duncan’s work includes the emerging field of "social epigenomics," an integrative field of research focused on the identification of socio-environmental factors—like limited access to health care, growing up in poverty, educational attainment, insurance status, and radon or secondhand smoke exposure—and examines their influence on human biology.

“Social epigenomics basically is studying how social determinants of health impact genetic expression,” Duncan said. “It is looking to see how your environment influences your genes leading to the development of cancer.”

Duncan’s research in racial and ethnic disparities contributes to a larger IU-led effort called End Lung Cancer Now, an initiative spearheaded by Nasser Hanna, MD, the Tom and Julie Wood Family Foundation Professor of Lung Cancer Clinical Research at IU School of Medicine and a member of the IU Simon Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Duncan’s research in racial and ethnic disparities contributes to a larger IU-led effort called End Lung Cancer Now, an initiative spearheaded by Nasser Hanna, MD, the Tom and Julie Wood Family Foundation Professor of Lung Cancer Clinical Research at IU School of Medicine and a member of the IU Simon Comprehensive Cancer Center.

Hanna recently gave a “State of Lung Cancer” address that included some positive trends and plans for a new mobile lung cancer screening program.

“The good news is that the number of people in the U.S. who die from lung cancer is rapidly falling, largely due to significant reduction in cigarette consumption,” he said. “We are making gains with lung cancer screening, but the rates continue to be unacceptably low. There have been significant therapeutic advances in the treatment of lung cancer, including the incorporation of immunotherapy and targeted therapy in early-stage disease.”

While that’s the good news, Hanna said, “there remains a lot of work to do.”

Some of that work is in addressing disparities in outcomes for minoritized populations, most notably among Black men.

“Black men are more likely to get lung cancer than their white counterparts, despite a lower intensity of smoking,” Hanna said. “They are more likely to be diagnosed with late-stage disease, less likely to be offered surgery, less likely to survive, and less likely to participate in a lung cancer screening program. Black Americans are more likely to be impacted by second-hand smoke as well.”

Duncan’s research is creating a better understanding of these disparities and what can be done to eliminate them.

“Understanding the causes of racial disparities in lung cancer outcomes is critically important to narrow these differences,” Hanna said. “Dr. Duncan’s research and my research overlap in many ways. Our goals are similar—to reduce the suffering and death from lung cancer and to eliminate the gap in outcomes seen based on difference in race and ethnicity.”

Learn more about End Lung Cancer Now and its goals for prevention, screening and clinical trials in lung cancer.