As a woman in the male-dominated field of science in the 1970s, Lynda Bonewald, PhD, was already a maverick. Bucking all her colleagues’ advice, her curiosity led her to study osteocytes—a type of cell within bones for which no one knew the function.

Earlier this year, this pioneer of osteocyte biology was honored by Indiana University as a Distinguished Professor, the university’s highest academic title, given to its most outstanding and renowned scholars and researchers.

“She has dominated the field of osteocyte biology for 30-plus years. You cannot find an article on this cell type that does not cite one of her published works,” said Alexander Robling, PhD, professor of anatomy, cell biology and physiology and professor of biomedical engineering at Indiana University School of Medicine.

Bonewald, also a professor of anatomy, cell biology and physiology, as well as orthopaedic surgery, is a researcher at the IU Simon Comprehensive Cancer Center and is founding director of the Indiana Center for Musculoskeletal Health (ICMH), a collaborative effort of more than 100 researchers from 36 academic departments statewide with a mission to discover and develop new treatments, cures, preventative strategies, diagnostic tools and technologies to address the increasing burden of bone, muscle and cartilage disorders.

Bonewald was recruited to lead the center in 2016, previously serving as vice chancellor for research and director of the Bone Biology Research Program at the University of Missouri-Kansas City. Bonewald’s research has been continuously funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for more than 30 years. The first-ever osteocyte cell line, which she developed, has been cited in more than 800 research papers.

Bonewald was recruited to lead the center in 2016, previously serving as vice chancellor for research and director of the Bone Biology Research Program at the University of Missouri-Kansas City. Bonewald’s research has been continuously funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for more than 30 years. The first-ever osteocyte cell line, which she developed, has been cited in more than 800 research papers.

“I kept looking at these beautiful cells that were located inside this hard bone tissue, and I started asking people, ‘What do these cells do?’” Bonewald recalled. “One colleague said, ‘They don’t do anything,’” and another said, ‘They’re too hard to study. It will ruin your career.’”

To the profound benefit of scientific understanding in bone biology, Bonewald did not heed that initial advice—just as she overruled the prevailing societal norm of her era that a woman’s place was solely at home. Bonewald, along with her supportive husband, Jack, successfully raised two daughters while simultaneously growing her career in academic medicine. She took a few years off when the girls were small but earned her PhD in immunology and microbiology from the Medical University of South Carolina at age 34.

“As a woman, you may have to give up some things—I didn’t have time to go shopping or get my hair and nails done—but you can have a successful scientific career and a family,” said Bonewald. Her advice to young women pursuing science is, “It’s not going to be easy, but if you really want something, you’ll work toward it and do it.”

Bonewald benefitted from some strong female mentors along the way, and she has herself become a role model and mentor to many next-generation scientists (both female and male).

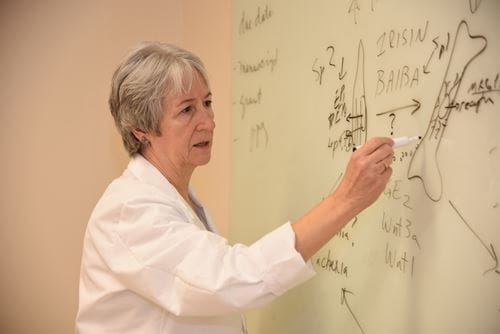

“She is one of the most incredible mentors in the university,” said Yukiko Kitase, PhD, assistant research professor of anatomy, cell biology and physiology. Kitase works in the Bonewald lab alongside her mentor, studying endocrine “crosstalk” between skeletal muscle and bone.

“She is a passionate and devoted leader,” said Kitase. “She always encourages us to improve our performance with critical and innovative thinking and act by core research values.”

The words Bonewald’s colleagues use to describe her include seemingly paradoxical combinations like “strong” and “caring” as well as “principled” and “curious.” These traits meld to form a leader who excels at team building and inspires scientific innovation.

“Whereas other professors at a similar stage in their careers may be preparing for retirement, she is still working incredibly hard to build a research environment to improve musculoskeletal health and to enable the next generation of scientists to succeed,” said Matt Prideaux, PhD, assistant research professor of anatomy, cell biology and physiology and an ICMH researcher. “She has mentored so many people from diverse backgrounds and many different countries. All of the people who have been trained by her leave as much better scientists and researchers than when they arrived.”

“Whereas other professors at a similar stage in their careers may be preparing for retirement, she is still working incredibly hard to build a research environment to improve musculoskeletal health and to enable the next generation of scientists to succeed,” said Matt Prideaux, PhD, assistant research professor of anatomy, cell biology and physiology and an ICMH researcher. “She has mentored so many people from diverse backgrounds and many different countries. All of the people who have been trained by her leave as much better scientists and researchers than when they arrived.”

Although Bonewald is a prolific researcher—she has 215 peer-reviewed publications, 44 review articles and 45 book chapters—she says there is too much pressure for young scientists to publish in top journals in order to get promoted.

“That should not be what science is about,” Bonewald said. “It should be about the quality of your findings and how many others have cited your information and built upon your results. Science builds on reproducibility and integrity. If you don’t have that, it’s an incredible waste.”

By all accounts, Bonewald holds to the highest standards of scientific integrity.

“She is dogged in her pursuit of scientific accuracy and validity,” said Distinguished Professor David Burr, PhD, former associate vice chancellor for research at IUPUI. “She is not only a synthetic thinker, she also is analytical in the lab, using a methodical approach to problem-solving. It is unusual to see both of these traits in a single scientist.”

H.H. Gregg Professor of Cancer Research and ICMH colleague Teresa Zimmers, PhD, calls Bonewald a highly effective leader with “unparalleled work ethic.”

“Her demeanor is remarkable for the unfailing respect she accords all her colleagues, both her distinguished peers and more junior investigators,” Zimmers said. “She demands much of her trainees, but their interaction with her unfailingly elevates their work and their careers.”

Bonewald’s advice to junior scientists is to let their curiosity lead and follow data-driven ‘rabbit trails’ that may result in new discoveries—such as the important role of osteocytes in bone formation and function.

Bonewald’s advice to junior scientists is to let their curiosity lead and follow data-driven ‘rabbit trails’ that may result in new discoveries—such as the important role of osteocytes in bone formation and function.

“Your scientific career might make several turns,” said the venerated pioneer in bone science. “Young scientists need to follow the data, not the dogma. The data will tell you which direction you should take.”

Bonewald’s unexpected career path has inspired and undergirded the work of countless scientific investigators across the globe.

“She’s incredibly strong and a thoroughly good and decent person in a world where there are too few like her,” Zimmers said. “She makes me strive to be a better leader, a better mentor and a better scientist.”