About two years ago, Leo Stenz started to experience memory issues in his day-to-day life. Even though his motor skills were still good—he worked out, ran and played golf—Stenz found himself forgetting the words to say in everyday conversations.

“I could see myself losing it sometimes in the middle of a sentence,” Stenz said.When his neurologist, Jared Brosch, MD, associate professor of clinical neurology at Indiana University School of Medicine, diagnosed Stenz with Alzheimer’s disease, he was taken aback, Stenz said. His mother had Alzheimer’s disease for nearly seven years, and he experienced first-hand her memory and cognitive ability decline while caring for her.

Despite this diagnosis, Stenz said he felt hopeful when Brosch told him about a new treatment in clinical trials that was moving toward full approval from the Food and Drug Administration.

“It gave me some excitement that something is coming around the corner,” Stenz said.

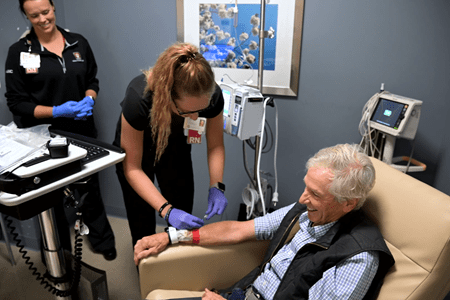

After a series of tests, Stenz qualified for and was the first patient at IU Health to receive lecanemab, the first-of-its-kind Alzheimer’s disease treatment. Also called Leqembi, the drug is the first amyloid beta-directed monoclonal antibody to receive traditional approval from the FDA.

Over the past few months, nearly a dozen patients have received the treatment, which is administered through intravenous infusions every two weeks at the IU Health Neuroscience Center in downtown Indianapolis.

For nearly a decade, lecanemab has been tested in clinical trials at IU School of Medicine, Brosch said. The drug targets the removal of amyloid plaques in the brain—a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease. Brosch said lecanemab met all clinical endpoints in phase 2 and phase 3 of the clinical trial and was shown to significantly reduce amyloid plaques in a person’s brain.

While the drug does not stop the disease or lead to cognitive improvement, Brosch said, it does “freeze” a person in their current functional state—potentially three or four more years of independence if the disease is caught early.

“That’s a big deal, Brosch said. “That’s a lot of time for a person to be living more independently and traveling and enjoying their grandchildren. It slows the progression to a point where it’s hard to notice that person is progressing while they’re on the drug.”

‘The cutting edge’

For more than 25 years, scientists and pharmaceutical companies have been attempting to develop a treatment for Alzheimer’s disease. Countless drugs have failed in clinical trials, and most of these treatments have tried to target the accumulation of amyloid plaques in the brain.

For more than 25 years, scientists and pharmaceutical companies have been attempting to develop a treatment for Alzheimer’s disease. Countless drugs have failed in clinical trials, and most of these treatments have tried to target the accumulation of amyloid plaques in the brain.

Instead of focusing on people who are in a later and more severe stage of Alzheimer’s disease like failed drugs in the past, lecanemab is geared toward people in early stages of the disease. More than 70% of people treated in the clinical trials of lecanemab could still live independently, Brosch said. They had Alzheimer’s disease, but the disease was at an early and mild stage.

“These people are going to primary care clinics, they are in the community, and they are experiencing memory problems, but they might not be telling anyone about it,” Brosch said. “Those are the people that really benefit the most and who we need to get to.”

Lecanemab is one of three potential Alzheimer’s disease treatments garnering attention, Brosch said, and IU School of Medicine was a clinical trial site for each of the drugs. These three drugs similarly target amyloid plaques and are intended for early symptomatic Alzheimer’s disease.

“It’s exciting that we’ve given that opportunity to our patients to be on the cutting edge,” he said.

The FDA approved the controversial drug aducanumab, or Aduhelm, under the accelerated approval pathway in 2021, but it hasn’t received full approval and is now in a phase 4 clinical trial to verify the drug’s clinical effectiveness.

An Eli Lilly and Company drug, donanemab, has shown promising results in its clinical trials, Brosch said, and is awaiting a decision for approval by the FDA.

“We’ve perceived a benefit in all of these drugs,” Brosch said. “It’s incredibly difficult to prove it with a number and a measurement, but in all of these drugs, we feel we’ve seen people do better when they receive these treatments.”

‘Changing how the disease looks’

Donna Wilcock, PhD, the Barbara and Larry Sharpf Professor of Alzheimer’s Disease Research in the Department of Neurology at IU School of Medicine, said those currently receiving lecanemab are patients neurology-based dementia specialists at IU School of Medicine believe will have the greatest benefit and lowest risk of side effects from the medicine.

Donna Wilcock, PhD, the Barbara and Larry Sharpf Professor of Alzheimer’s Disease Research in the Department of Neurology at IU School of Medicine, said those currently receiving lecanemab are patients neurology-based dementia specialists at IU School of Medicine believe will have the greatest benefit and lowest risk of side effects from the medicine.

The earlier a patient receives the treatment, the greater the benefit, Wilcock said.

Wilcock is the director of the Center for Neurodegenerative Disorders in the IU School of Medicine-IU Health Neuroscience Institute, which oversees the administration of lecanemab through its Brain Health Program. This wraparound program, Wilcock said, sets patients and their families up with a brain health navigator to schedule appointments and act as a resource.

Brosch said this team of neurologists have been prequalifying their patients based on the results from clinical trials. These patients have already had the necessary MRI and PET scans and other screenings needed to qualify them to receive the new Alzheimer’s disease treatment.

In addition to the nearly one dozen patients who started receiving the treatment in September, there are at least that many in the pipeline at IU Health. Brosch said the program also is expanding into geriatric clinics to find qualified patients and is establishing a statewide set of guidelines to refer patients and prequalify them as the drug becomes more known.

“It’s certainly hopeful,” Wilcock said. “It’s the best result we’ve had in clinical trials ever for Alzheimer’s disease. It’s the first disease modifying treatment. We’re not just treating symptoms, we’re changing how the disease looks in the brain, and changing it for the better.”

‘End of the beginning’

While the data from clinical trials of lecanemab is promising, there are still many questions that researchers and physicians at IU School of Medicine are investigating. Brosch said they will need to determine how long to administer the drug to patients.

It’s also unclear how much time it takes for amyloid plaques to reaccumulate in the brain once they are reduced by taking lecanemab, Brosch said, and if the drug ultimately alters the trajectory of the disease. In addition to the drug infusion, patients will be given high-quality MRI scans throughout their first year of treatment.

There are also still ongoing phase 3 studies of lecanemab that are analyzing the safety and efficacy of an injection of the treatment rather than an infusion, Brosch said. This would create better access, and potentially lower costs, he said, by allowing people to inject themselves with the drug at home rather than traveling to an outpatient center every two weeks.

Brosch said the Dominantly Inherited Alzheimer’s Network Treatment Unit—IU School of Medicine is a site for a clinical trial—is the first study to combine lecanemab with an anti-tau protein drug. After amyloid plaques form in the brain of Alzheimer’s disease patients, researchers say the protein tau begins to form tau tangles in the brain.

IU School of Medicine researchers plan to investigate signatures in the blood of patients receiving the lecanemab to see if there are biomarkers that could predict who will respond well to the drug and who will have adverse effects. The medical school has a strong biomarker program in the National Centralized Repository for Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias (NCRAD) Biomarker Assay Laboratory, Wilcock said, where they can study these biomarkers.

Researchers are also hoping to apply machine learning and artificial intelligence approaches to MRI clinical scans to study patient outcomes, Wilcock said.

“Where we see the field moving is to a precision medicine approach where we’ll be able to look at blood signatures and be able to identify exactly what changes someone’s brain is going through,” Wilcock said. “The hope is at the same time that we’ll be able to create an arsenal of drugs—like lecanemab—that will be able to specifically target these changes. The approval of this drug is not the beginning of the end but the end of the beginning."