Dear colleagues,

“One thing only I know … and that is I know nothing.” So said Socrates, one of the founders of Western philosophy, about 2,400 years ago. This was in response to hearing that the Oracle of Delphi declared there was no one who was wiser than Socrates. He tried to prove the Oracle wrong by interviewing “wise men,” but he found that unlike these so-called wise men, Socrates did not claim to know what he did not know. This was the true meaning of the Oracle’s message. Socrates frequently engaged students and citizens in Athens in philosophical discussions using questions and answers (the Socratic Method). Socrates also was an outspoken critic of the Athenian government, which eventually led to his conviction and a sentence of death by drinking hemlock.

Persecution and defamation also have not been uncommon in science. In Renaissance times, there emerged heretical thoughts that the Earth might rotate around the sun, rather than the other way around (heliocentric theory). Nicolaus Copernicus published this theory in 1543 in his famous work De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium, which directly challenged the teachings of the Bible. Perhaps fortunately, he died shortly after its publication sparing him persecution. It did not fare as well for Galileo Galilei, who was born a couple decades after Copernicus death. Galileo was found by the Catholic church to be “vehemently suspect” of heresy for his publications supporting the Copernican heliocentric views. He was tried, convicted, and sentenced to house arrest, where he remained for the rest of his life and his offending texts were banned. Four centuries later, Pope John Paul II acknowledged that the Catholic church had erred in condemning Galileo.

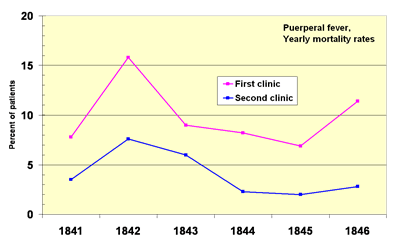

In 1847, Ignaz Semmelweis, an obstetrician in Vienna, published evidence that when doctors washed their hands before examining or treating patients the mortality rate for women in his birthing ward was greatly reduced. At the time, hygiene was not a staple of medical care. For example, it was common for medical students and doctors to examine corpses in the mor tuary then assist women during childbirth without washing their hands in the interim. Semmelweis compared the outcomes of fatal infections and puerperal fever in the wards covered by these medical students and staff (first clinic) to a second clinic attended to by midwives who had no exposure to the cadavers. He found a striking difference (see figure). Semmelweis subsequently proposed the practice of washing hands with chlorinated lime solutions in Etiology, Concept and Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever. Despite this, the medical establishment rejected his ideas. Remember, this was well before Pasteur and Lister had discovered microbes and confirmed the role of antiseptics, so Semmelweis could offer no acceptable scientific explanation for his findings. Many of his colleagues mocked him for his suggestions and consequently Semmelweis suffered a nervous breakdown and was committed to an asylum. He died 14 days later from a gangrenous wound on his right hand after being beaten by guards.

tuary then assist women during childbirth without washing their hands in the interim. Semmelweis compared the outcomes of fatal infections and puerperal fever in the wards covered by these medical students and staff (first clinic) to a second clinic attended to by midwives who had no exposure to the cadavers. He found a striking difference (see figure). Semmelweis subsequently proposed the practice of washing hands with chlorinated lime solutions in Etiology, Concept and Prophylaxis of Childbed Fever. Despite this, the medical establishment rejected his ideas. Remember, this was well before Pasteur and Lister had discovered microbes and confirmed the role of antiseptics, so Semmelweis could offer no acceptable scientific explanation for his findings. Many of his colleagues mocked him for his suggestions and consequently Semmelweis suffered a nervous breakdown and was committed to an asylum. He died 14 days later from a gangrenous wound on his right hand after being beaten by guards.

Another example of delayed scientific acceptance is the story of James Lind who was a military surgeon who served in the British Royal Navy from 1739 t0 1748. Lind conducted one of the first randomized clinical trials in medicine. In his time, scurvy was a leading cause of death among sailors, reportedly causing more deaths in the British fleet than by the hands of their French or Spanish foes with whom they were engaged in armed conflict. Scurvy is caused by vitamin C deficiency, but in Lind’s day, the concept of vitamins was still unknown. After two months at sea, many of his fellow shipmates on the HMS Salisbury were afflicted with scurvy. Lind divided 12 of these sailors into six groups of two. They all received the same diet. In addition, group one was given a quart of cider daily, group two 25 drops of elixir of vitriol (sulfuric acid), group three six spoonful’s of vinegar, group four half a pint of seawater, group five received two oranges and one lemon, and group six a spicy paste plus a drink of barley water. The treatment of group five (oranges and lemon) stopped after six days when they ran out of fruit, but by that time one sailor was fit for duty while the other had almost recovered. In 1753, Lind published A Treatise of the Scurvy, which was ignored for decades.

Today, we are faced with a pandemic caused by a novel coronavirus, discovered just a few months ago. Like the scientists and philosophers over the last two millennia, we are struggling to understand this virus, including its treatment and prevention. We have the advantages of modern technology and the rapid exchange of knowledge that is unprecedented in our history. This still does not mean we get it all right, but we try.

No one is trying harder than Dr. Anthony Fauci, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, who has been the public face of rational scientific reasoning during this pandemic.

Amid speculations of displeasure by the White House, the editorial board of USA Today wrote last week, “Fauci, 79, is a national treasure. He is one of the leading authorities in his field. He combines extraordinary expertise with an exceptional ability to communicate with ordinary people. He has held his position for 36 years, earning the admiration of multiple presidents, including George W. Bush, who awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom.” Through the HIV, SARS, MERS, and Ebola crises, Dr. Fauci has led with candor and caution.

However, in an opinion piece in the same issue, White House trade adviser Peter Navarro painted a different view: “Anthony Fauci has been wrong about everything I have interacted with him on.” Navarro went on to describe how Fauci was wrong on masks, travel bans from China, and the benefits of hydroxychloroquine and when it comes to listening to Fauci, he only does so with “with skepticism and caution.” Also, Dan Scavino, the administration’s deputy chief of staff for communications, posted a cartoon lampooning Fauci as an economy-destroyer. In the caption of the post, he wrote, “Sorry, Dr. Faucet! At least you know if I’m going to disagree with a colleague, such as yourself, it’s done publicly — and not cowardly, behind journalists with leaks. See you tomorrow!” Fortunately, others have come to Dr. Fauci’s defense.

The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) issued the following statement:

“The AAMC is extremely concerned and alarmed by efforts to discredit Anthony Fauci, M.D., our nation’s top infectious disease expert. Dr. Fauci has been an independent and outspoken voice for truth as the nation has struggled to fight the coronavirus pandemic. As we are seeing from the surge in COVID-19 cases in areas that have reopened, science and facts — not wishful thinking or politics — must guide America’s response to this pandemic. … a successful response depends on Dr. Fauci, his colleagues, and scientists throughout America’s system of medical research who are able to draw conclusions based on current observations and continuously adjust those conclusions based on continuing observations. Science is, and must be, a dynamic and evolving process.”

And on behalf of the Infectious Disease Society of America, President Thomas File wrote:

“As 12,000 medical doctors, research scientists, and public health experts on the front lines of COVID-19, the infectious diseases community will not be silenced nor sidelined amidst a global pandemic. Reports of a campaign to discredit and diminish the role of Dr. Fauci at this perilous moment are disturbing. … This is a full-blown crisis unlike any America has ever faced and it needs to be treated as such. The only way out of this pandemic is by following the science, and developing evidence-based prevention practices and treatment protocols as new scientifically rigorous data become available. Knowledge changes over time. That is to be expected. If we have any hope of ending this crisis, all of America must support public health experts, including Dr. Fauci, and stand with science.”

As scientists, we are used to being critiqued on our work. Of course, we are upset when receiving inappropriate reviews of our grant submissions or uninformed comments on our submitted papers. This current atmosphere on a national level feels much different. There are efforts to dismiss the field of science and discount sound public health practices. More disturbing is a concerted effort to disparage the messengers. Despite the advances in science, technology, and communications, we are reminded that there still remain people who persecute others that share what are inconvenient truths. It is our duty to be resilient in defense of our vocation but also admit when we are wrong, or as Socrates said, “True wisdom comes to each of us when we realize how little we understand about life, ourselves, and the world around us.”

Be Safe!

Sincerely,

Patrick J. Loehrer, Sr., M.D.

Distinguished Professor

Associate Dean for Cancer Research

Director, Indiana University Melvin and Bren Simon Comprehensive Cancer Center

H.H. Gregg Professor of Oncology Professor of Medicine

Indiana University School of Medicine