A century ago, Dr. James O. Ritchey graduated from IU School of Medicine. For the next six decades, he prepared legions of healers who followed in his footsteps.

By Matthew Harris

The Black Bag.

The future physicians remember the relic just as distinctly as the buttoned-up gentleman who carried it. They remember how elegant he looked—attired in a suit, starched collar and tie no matter the time, day or weather. While his peers pressed elevator buttons, he briskly climbed the stairs at Methodist Hospital. And he was no mere instructor.

“He was an oracle of truth and wisdom,” one of them remembered.

To the afflicted, James O. Ritchey, MD, could be a gentle presence, one who took your hand, let a full grin cross his face, leaned in and listened. In awe, medical students watched as the healer drew out details to point the way. Listen to the patient’s story, he would instruct. Ninety-five percent of the time, you will learn their diagnosis.

For six decades, he faithfully served Indiana University School of Medicine with the same quiet grace and dedication he gave to his patients.

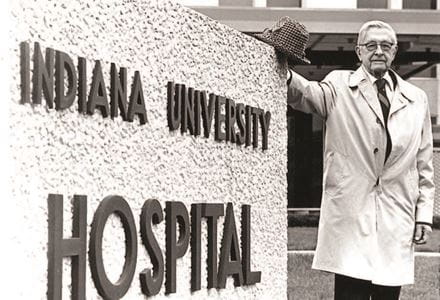

One hundred years ago, the young man from Carroll County graduated from IU School of Medicine, embarking on a career that saw him rise to lead its Department of Medicine, chair its admissions committee and earn honors such as the Distinguished Alumni Award.

Though much has changed at IU School of Medicine–and in the profession as a whole–Ritchey remains a legend at his alma mater, and many who trained under him or worked alongside him still consider him the embodiment of what it means to be a physician. At the centennial of his graduation, IU Medicine looks back on the life of James Oscar Ritchey and how he helped shape a then-fledgling medical school.

1891 | OWASCO, INDIANA

Rummage around Ritchey’s childhood, and you won’t unearth wealth or refinement. You might not find much at all. “I’ll bet you’ve never heard of my hometown,” Ritchey joked to an Indianapolis News columnist in 1974.

Ritchey was born on Feb. 1, 1891, in the rural burg of Owasco, Indiana, less than 20 miles from Lafayette. There, Aaron and Christina Ritchey raised their eight children on a modest patch of ground. Their relatives were sprinkled between what is today Rossville and Delphi, the final stop on the family’s three-generation sojourn from the Scottish Highlands.

Much of Ritchey’s upbringing is lost to history except for the simple tale of what drove him toward medicine. A beloved country physician served as a role model, so much so that he inspired a pact between Ritchey and a friend.

“We decided in the third grade we were going to be doctors,” Ritchey told The Indianapolis Star in May 1978. “We both made it. He became a surgeon at Muncie and graduated a year before I did.”

1916 | INDIANAPOLIS

The medical student dropped his bags on the floor of a boarding house, and then he set out to find a job.

In time, Ritchey’s ascendancy would egin. That fall, though, he was just a 25 year old hustling to pay bills, waiting tables at a downtown restaurant, and riding an ambulance that carried injured workers from the New York Central Railroad to Indianapolis City Hospital.

“For that, I was paid my room and board,” he told the Star.

Three years earlier, Ritchey and other farm boys had trickled into Bloomington, then a town of 4,000, to study medicine. Like the medical school that accepted them, their credentials were modest. “Most of the students wouldn’t be accepted today,” said Walter J. Daly, MD, dean emeritus of IU School of Medicine and a member of the Class of 1955. “Their grades weren’t good enough.”

Their school was also rough around the edges, less than a decade removed from a bitter dispute with Purdue University over who would run a medical program in Indiana. Charles P. Emerson, MD, the school’s newly hired dean, barely trusted his faculty. It wasn’t until 1914, on a 19-acre parcel near the White River, that Robert W. Long Hospital opened with 106 beds. Five years later, the school opened the Medical School Building at a current cost of $4.5 million.

In Ritchey’s day, medical students began their training in Bloomington, moving north holding a clinical discussion on Saturdays, and operating his practice. Three years later, he was promoted to full professor. “Ritchey was inspired by Emerson,” Daly said, “and Emerson was inspired by (William) Osler.”

By the 1940s, Ritchey’s once a week teaching session was a staple—a public ritual at which a fourth-year student would briskly give a patient history and share findings from a physical exam. Ritchey’s critiques could be succinct, withering and incisive all at once.

“I felt terribly respectful,” Daly said. “He was someone I would like to be like.”

There was the time Louis Sandock, a 1941 graduate, ticked off a patient’s medical history. He confidently told all assembled—residents, interns, nurses, and dietitians—his exam revealed an enlarged spleen. After quietly digesting the student’s report, Ritchey for the final two years of instruction and clinical work at Indianapolis City Hospital.

For his part, Ritchey shaped his life around the rhythms of his training. He didn’t enjoy much of a social life. One semester, he loaded up on 20 hours of coursework. Ritchey thrived. By his fourth year, he handled modest teaching duties, usually instructing younger classmates how to do physical exams. Years later, stories circulated among students about Ritchey’s intellect. Like the one about how he peered down the tube of a microscope at a fibrous strand, which some thought might be an intestinal parasite.

“It’s a banana peel,” he declared.

At his graduation in 1918, the school presented Ritchey with the first-ever Marcus Ravdin Medal, awarded to the student with the highest grade-point average. A couple of months later, the newly minted physician passed his licensing exams in Indianapolis. The path his career would follow, though, had been plotted out well before.

1932 | LONG HOSPITAL

Without question, Emerson was the guiding hand in Ritchey’s career. The dean oversaw Ritchey as an intern at Long Hospital. Later, he dispatched the young physician on a tour of Eastern medical schools to glean insights on clinical teaching. Finally, Emerson invited the young Ritchey to practice with him.

By 1928, Ritchey was an assistant professor, teaching five days a week, struck.

What if it were a mass elsewhere in the abdomen? Or an aberrant lobe of the liver? Or a tumor? “How do you know?” Ritchey asked.

Flustered, the young student stammered as he searched his mind and the room for help that wasn’t coming, Sandock wrote in a 2002 remembrance of Ritchey’s life. Suddenly, the patient popped upright and clasped his hand. “You leave him alone,” she scolded. “If he says it’s my spleen, it’s my spleen.” Silence settled over the group. Until Ritchey laughed. “He’s right ma’am,” Ritchey said.

Ritchey saved his reserves of tenderness for patients. He would hold their hands, lean in to hear soft answers to his questions, and never be abrupt. “Always touch the patient when you are imparting bad news,” he preached.

The ward was Ritchey’s habitat, and staying late was his habit. During World War II, when large numbers of faculty were shipped overseas to aid in the war effort, it fell to men like Ritchey to teach two classes worth of students as IU went to trimesters. Over those four years, he might be at work as late as 11 o’clock. Even then, he would retire to the residents’ lounge to pick his colleagues’ brains.

“Although he would appear very tired at the beginning of those late evenings, he seemed rested and relaxed when they ended,” the late Glenn W. Irwin Jr., MD, wrote in a book of remembrances published about Ritchey in 2002. A 1944 alumnus of IU School of Medicine, Irwin went on to serve as dean.

And as unruffled as Ritchey could be, little incongruities popped up. On Fridays, he’d take a seat in the third row of the auditorium of Long Hospital and wait for clinical discussions to begin. An unlit cigar would dangle between two fingers. On his head, a cowlick stood at attention.

“It became common for a student to say when his hair was awry that he had a Ritchey,” Edith B. Schuman, MD’33, who passed in 2007, recalled in her remembrance.

MAY 1978 | UNIVERSITY HOSPITAL

IU never paid Ritchey a cent. “I checked with officials down in Bloomington,” Daly said. “And they confirmed it.”

Overseeing the Department of Medicine, which Ritchey did until 1956, was an unpaid position. Ritchey’s peers were like him: working physicians and scientists reliant on their practice or outside jobs. And even when Ritchey formally retired from the faculty in 1961, he remained in a position of prominence overseeing admissions.

In many ways, medicine was a refuge. In 1957, Ritchey’s first wife, Helen, passed away unexpectedly, leaving J.O. a widower for eleven years, until he married his second wife, Lydia. His practice, overseeing the admission’s committee, and philanthropic roles such as running the School of Medicine’s annual fund occupied his time.

On the eve of the School of Medicine’s 75th anniversary, and three years before his passing, Ritchey said he could sense the pace quickening—a tide he ably tried to swim along with. On vacations, a stack of medical journals sat within reach. If you scanned the back of a room at the annual gathering of the American College of Physicians, you might spot an 88-year-old Ritchey taking in a session on immunology.

As always, he was ever the student.

“Things are happening now and will happen in the future,” he said in 1978, “that no one could have dreamt of in my day.”