Lucky Medicine

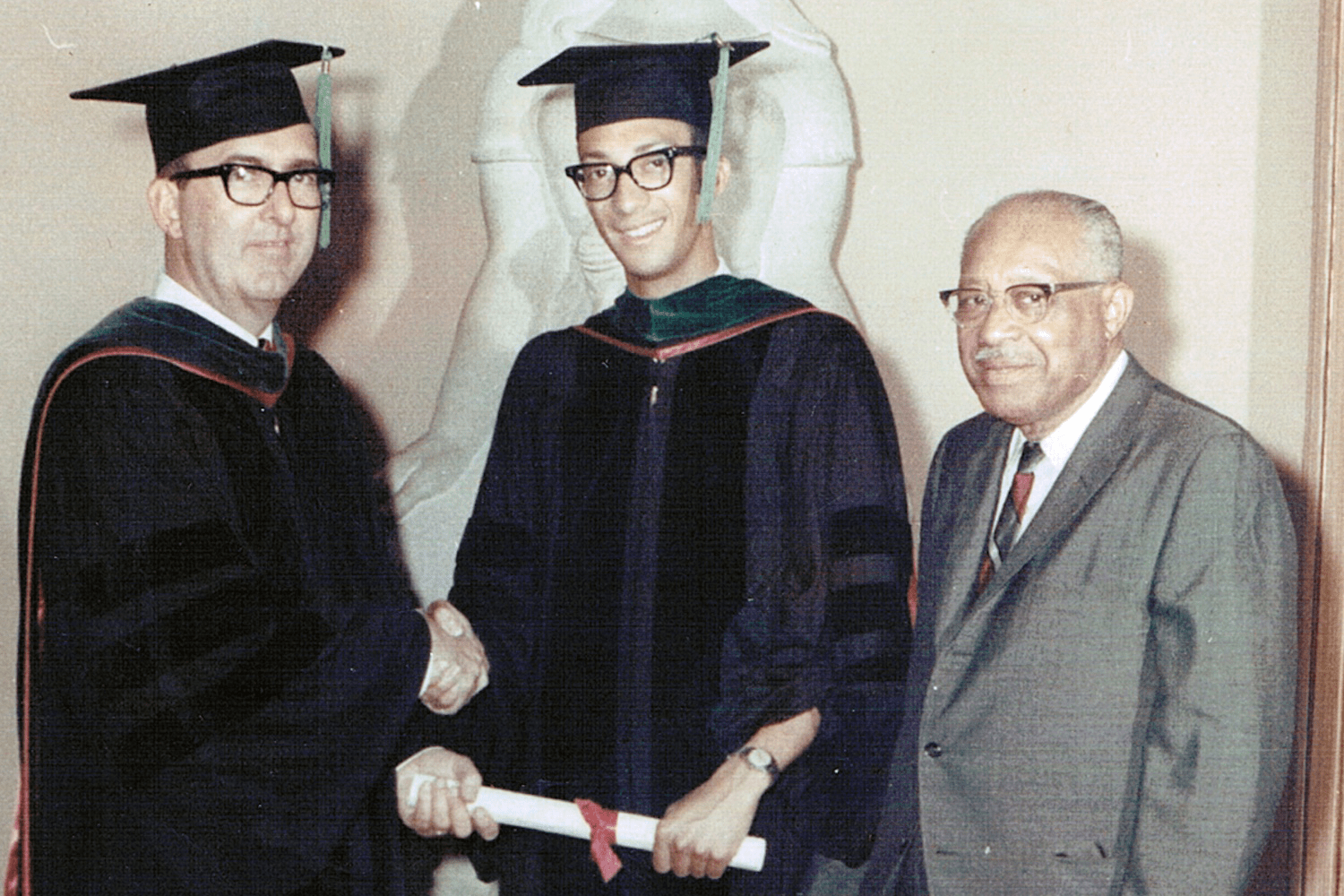

Lester Thompson, MD, flanked by Dean Glenn Irwin, Jr., MD, and Thompson's father, Calvin, at the 1968 IU School of Medicine graduation.

Bobby King Feb 01, 2023

LESTER THOMPSON, MD, never had one of those childhood moments where he saw a doctor at work and just knew he wanted to be a physician. He never had an epiphany, such as after losing a loved one to illness, that inspired him to pursue a career as a healer. Instead, the idea that he would become a doctor was almost entirely his father’s idea.

Calvin Thompson had grown up in Nashville, Tennessee at the turn of the 20th Century with a dream of becoming a doctor. But, with the death of his own father, he had been forced to quit school at a young age to help support his brothers and sisters. At some point, he decided that if he ever had a son, the boy would grow up to become a doctor. That was the legacy Lester inherited.

“He just told me from my earliest recollection that this is what you are going to do. I don’t ever remember him asking me if this was what I wanted to do,” Thompson recalls. “My dad, by today’s standards, was an autocrat who said, ‘Here’s the agenda, do you understand your role? End of discussion.’”

Thompson followed his father’s roadmap and, with the extraordinary generosity of an Indianapolis philanthropist, he graduated from Indiana University School of Medicine in 1968. He would go on to enjoy a 37-year career as a urologist, retiring in 2012. His memoir of the journey, published this month by IU Press, is called As the title suggests, the book delves into Thompson’s life and the segregation he faced as a young Black boy growing up on Indianapolis’ Near Northside. It follows him to Bloomington, where he enrolls at IU, immerses himself in the Black Greek community, and comes fist-to-fist with tensions of the era during a race riot in Bloomington. And it continues in Indianapolis, where he enters IU School of Medicine as one of only a handful of Black students learning from an almost all-White faculty. Here, though, he realizes his father’s dream of becoming a physician—epitomized by a graduation photograph of Dean Glenn Irwin, Jr. MD, Thompson and his father. By then, it is a dream that Thompson has made his own.

Lester Thompson, MD

The foundation for the book was laid in the 1960s, with a journal Thompson kept through his college years that ran 800 pages long. During the decades he was practicing medicine and raising a family, the journal gathered dust. A few years after retirement, he returned to his story.

Thompson’s father is a central character. A barber who for years had a shop in a Downtown Indianapolis office building, Calvin Thompson cut the hair of many of the city’s White powerbrokers during the middle of the 20th Century. It gave him access to an extensive network of some of the most influential leaders. “My dad knew where the bodies were buried, and he knew how to keep a secret,” Thompson said.

He also introduced young Lester to one of his best customers—wealthy businessman and philanthropist Lazure L. Goodman, whose death in 1966 would warrant an obituary in The New York Times.

His father would take him along on haircut house calls to Goodman’s home. Young Lester marveled at the size of it and the lavish furnishings but for years wondered why his father kept bringing him. Eventually, he learned that his father and Goodman had struck a deal years before: If Thompson were willing to name his son after Goodman, Goodman would pay the costs of the boy’s college and medical school. For the arrangement, the barber chose Goodman’s middle name—Lester—for his son’s.

Of this arrangement between the Black barber and the Jewish industrialist and its impact on his life, Thompson says simply: “My father was the engine and (Goodman) provided the fuel. Without him, it just wouldn’t have happened.”

Thompson said that, in all the attention that historians have rightly spent on the Jim Crow era familiar to his parents and the racial unrest of the late 1960s, he feels his formative years in between have been somewhat overlooked.

He took up the book project in 2016, intent on telling his perspective on that period, especially the Black Greek social life of the day, before time slipped away from him. The murder of George Floyd in 2020 and the social justice uprisings that followed gave him an added impetus to finish it. He’s planning to devote a portion of the proceeds to the IU Black Philanthropy Circle, which supports scholarships, academic, cultural and arts programs.

Now 79, Thompson hopes that the story of “how this poor kid from Indianapolis—skinny and insecure” became a physician will resonate with others. “I was fortunate to have a mentor, but I did this. They opened the door, but I had to go through it,” he said. “I’m hopeful it will inspire people to pursue their dreams and follow their passions, be it medicine or some other field.”

Book Info:

Lucky Medicine: A Memoir of Success Beyond Segregation

By Lester W. Thompson

IU Press, 210 pages

Ebook: https://iupress.org/9780253065261/lucky-medicine/

Bobby King

Bobby King is the director of development and alumni communications in the Office of Gift Development. Before joining the IU School of Medicine in 2018, Bobby was a reporter with The Indianapolis Star. Before that he was a reporter for newspapers in Kentucky, South Carolina and Florida.