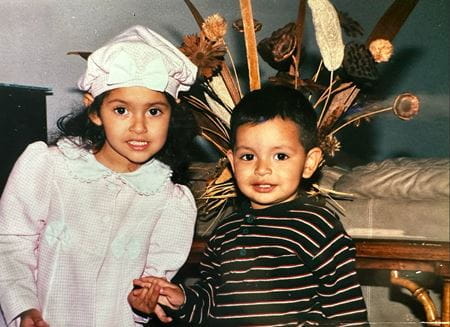

Siblings Alejandra and Hugo Rodriguez grew up in two worlds—first a close-knit, predominantly Mexican neighborhood in south Chicago, then Crown Point, a largely white community in northwest Indiana with a much higher per capita income.

The stark contrast has shaped their stories and influenced their passions, leading both to pursue medical degrees at Indiana University School of Medicine. Alejandra is a fourth-year medical student applying for residency programs in pediatrics while Hugo is a second-year medical student on the West Lafayette campus.

“I acknowledge I wouldn’t be where I am now if I hadn’t moved to Crown Point,” said Hugo. “But if I hadn’t lived in Chicago, I would not be the type of care provider I plan to be.”

Culture shock

Hugo counts his grandfather, parents and big sister Alejandra among the most influential people in his life.

“My sister is one of my biggest mentors and sources of inspiration—I wouldn’t be here without her,” he said. “Going through high school and in undergrad, everybody had a family friend, an aunt or uncle or somebody who was a doctor. We had nobody. I admire my sister for being able to navigate the system and the application process for medical school. I had her to help me, but she had no one.”

It was their grandfather, Esteban Rodriguez, who forged the way for his progeny to build a better life in the United States. He initially left his small town of Momax in the Mexican state of Zacatecas to work in the U.S. as a seasonal farm worker through the Bracero Program. He later applied for residency and was able to bring his wife to Chicago. While they established their new life, their children stayed with relatives in Mexico.

Son Aurelio was 7 when he and his siblings joined their parents in Chicago. The family visited their Mexican hometown often, and on one of these visits, Aurelio met his future bride, Martha. The couple would build their own life in Chicago with Aurelio working as an electrical technician and Martha caring for their four children, including Alejandra and Hugo.

The family felt comfortable in the area known as the “Mexico of the Midwest,” and the Rodriguez children remained connected to their cultural heritage.

“We grew up speaking ‘Spanglish’ with kids who looked like us, who had parents with stories like ours,” Alejandra said. “The school had a lot of bilingual programs and resources, and there was a Mexican grocery close enough to walk to. Being in that community, we felt like we belonged.”

But there were challenges, too. Crime rates were high, and local schools rated poorly. Aurelio wanted to give his children opportunities he never had, so he moved the family to Crown Point.

“I’m really, really proud of my dad,” Hugo said. “He’s done so much for us—he’s given us everything.”

The siblings also credit their mother with instilling the values of selflessness, hard work and sacrifice for the good of the community.

“My mother grew up on a farm outside of the tiny town of Momax,” Hugo said. “My mom has little to no formal education, but her family knew this was no excuse to not have respect for others and lend a helping hand to those in need. The most basic trait a physician should have is respect for others regardless of any individual characteristic that person may have. My mother taught me this.”

Unlike their school community in Chicago, everyone at their Crown Point school expected to go to college, Hugo said. “It was a big shift in thinking.”

The new educational opportunities, however, came with a huge culture shock.

“I came in middle school, and I didn’t have any other Latino friends,” Alejandra said. “None of my teachers looked like me. No one around us understood our experience. There was no Mexican food market, and my mom especially had difficulty communicating—no one could talk to her in Spanish.”

Their new neighborhood had an individualistic vibe. People kept to themselves.

“Mexican culture is very community oriented—you’re not just worried about yourself, you’re worried about your neighbors and helping others without being asked,” Alejandra said, noting the value of their early childhood experience in Chicago. “That primed us to be in a medical career. We want to help others and be part of a greater community of support.”

Hugo: ‘Am I allowed to dream this big?’

Hugo determined he wanted to be a doctor at an early age, but he wondered, “Am I allowed to dream this big?”

Most of the Mexicans he saw in his community were laborers. He never met a Mexican doctor until coming to IU School of Medicine, where his studies include a scholarly concentration in the Care of Hispanic/Latino Patients. He quickly bonded with program co-director Ray Munguia-Vazquez, MD, PhD, a native-born Mexican who did his medical training in Mexico City and is now a clinical assistant professor of otolaryngology–head and neck surgery and coordinator of pre-clinical studies on the West Lafayette campus.

“He wears a gold bracelet on his wrist, and we talk about food and sports,” Hugo said. “It’s somebody who gets your culture.”

Munguia-Vazquez is delighted to see a student with Mexican heritage who is proud of his cultural identity, rather than trying to hide or diminish it.

“Even though Hugo grew up in the United States, the Mexican culture was kept by his family and his environment, and he is very vocal—I’ve seen very few Mexicans like that,” Munguia-Vazquez said. “He is a leader in the classroom, a student rep for the class, and if he doesn’t like something, he comes and tells a faculty member about it.”

In an effort to improve the scholarly concentration program, Munguia-Vazquez is developing international clinical experiences with Chuck Dietzen, MD, founder of Timmy Global Health and a distinguished alumnus of IU School of Medicine. Hugo volunteered to pilot the program and put his medical Spanish skills to the test in Ecuador last summer.

“He has the open heart and open mind to be the first to go out there and do this,” said Dietzen. “He’s got two primary languages, and he understands Latin American culture. He was the perfect person to kick off this new program.”

Hugo and Lisa McTavish, MD, worked alongside Ecuadorian physicians and nurses to provide primary care to patients with chronic illnesses, both in-clinic and in patients’ homes—some of which had dirt floors and no running water. The experience evoked a sense of gratitude while strengthening Hugo’s passion for providing culturally competent care.

Hugo and Lisa McTavish, MD, worked alongside Ecuadorian physicians and nurses to provide primary care to patients with chronic illnesses, both in-clinic and in patients’ homes—some of which had dirt floors and no running water. The experience evoked a sense of gratitude while strengthening Hugo’s passion for providing culturally competent care.

“Hugo is a clear communicator, respectful, very observant, a problem solver and a leader,” McTavish said. “He stands up for what he believes, and he is trustworthy.”

Hugo is taking what he learned back to Indiana, where U.S. Census Bureau data shows a growing Hispanic/Latino population, now at 8%, contrasted with a physician population that’s just 4% Hispanic, according to a 2021 report by the Bowen Center for Health Workforce Research and Policy at IU School of Medicine. The majority of Indiana’s Hispanic population is of Mexican descent.

“A lot of people feel doctors don’t understand them or get where they’re coming from,” Hugo said. “I want to see more Mexican medical students and Mexican doctors.”

That’s why Hugo is pursuing opportunities to speak to Hispanic high school and college students. He wants to encourage them to dream big—like he and Alejandra did.

Alejandra: ‘Coming from that community, you have more understanding.’

Growing up, Alejandra and Hugo often served as translators for their mother at medical appointments. Today, many physicians use software programs to aid communication, but Alejandra has seen instances where meaning is lost in translation. And electronic tools can’t pick up on societal and cultural barriers to health care.

“It’s been wonderful to see how technology is helping bridge those communication gaps, but there is no replacement for a provider who can speak the same language and, beyond that, understand the culture and understand why a patient would withhold obtaining care until they’re on their deathbed,” Alejandra said. “Coming from that community, you have more understanding.”

For many Latino immigrants, barriers to care may include mistrust of health professionals, preference for homeopathic remedies, fear of deportation, cost of services, and time off work required for health care appointments.

“I’m really interested in addressing health literacy and helping diminish cultural barriers to care,” Alejandra said. “Seeing how limited English skills and other challenges impacted my mom and her hesitance to schedule appointments, now, as someone who is bilingual, I can be a provider who can teach people in their own language. It’s very important for our patients to be informed of their treatment options and be more empowered to make decisions for their care.”

Alejandra gained valuable experience working with Latino immigrants at two Eskenazi Health clinics in Indianapolis, an opportunity coordinated by John Christenson, MD, statewide director for pediatric clerkships at IU School of Medicine.

“Her interactions with parents and patients were excellent,” said Christenson, professor of clinical pediatrics and associate medical director for pediatric infection prevention at Riley Hospital for Children at IU Health. “She is one of the smartest medical students I know. ... Not only does she know the patients well, but she is highly familiar with the diagnostic and therapeutic issues surrounding their care.”

Alejandra further developed her passion for clinical education while serving at the Boys and Girls Club of Bloomington though AmeriCorps at IU School of Medicine. She helped youth learn to identify their emotions and develop positive coping strategies, as well as practice healthy habits including nutrition.

“Alejandra is one of the most warm, thoughtful and critically-minded students that I have worked with,” said Niki Messmore, MS, director of medical service learning at IU School of Medicine. “She did an amazing job serving as an IU School of Medicine AmeriCorps member, and her nonprofit raved about her work ethic and ability to educate youth on wellness topics. I absolutely know that she’ll be a brilliant and patient-centered physician in the future.”

“Alejandra is one of the most warm, thoughtful and critically-minded students that I have worked with,” said Niki Messmore, MS, director of medical service learning at IU School of Medicine. “She did an amazing job serving as an IU School of Medicine AmeriCorps member, and her nonprofit raved about her work ethic and ability to educate youth on wellness topics. I absolutely know that she’ll be a brilliant and patient-centered physician in the future.”

Alejandra and Hugo have demonstrated excellence throughout their medical school experiences—not despite their background but because of it.

“My dad taught me to work hard,” Hugo said. “He said, ‘You’re going to work like a Mexican whether you like it or not—so you might as well work at school.’ Being Mexican has made me stand out, but it also motivated me. Not seeing people like me (in medicine), that keeps me going.”

Sharing cultural traditions: Hot Cheetos & Christmas Mains

The way you eat Cheetos in South Chicago is doused in hot sauce with a squeeze of lime.

The way you eat Cheetos in South Chicago is doused in hot sauce with a squeeze of lime.

“My younger siblings and I will open the chips, pour them on a plate with hot sauce, and sit and talk at family gatherings,” said Hugo.

Alejandra isn’t as big a fan of hot Cheetos. Her favorite family memories come from visits to her mother’s side of the family in Momax for Christmas, a holiday hugely celebrated in Mexico.

“On the 24th of December, all the women in the family get together to prepare the Christmas Mains,” Alejandra said. “One person would work on putting the dough on the corn husk for tamales while others work on the filling in a big assembly line. The process of cooking food together is an ingrained part of the holidays. That’s a huge tradition.”

Other traditional Christmas foods include Mexican ponche (warm punch), buñuelos (a dessert made from fried dough covered in cinnamon sugar) and pozole (spicy pork stew).

Ready for a taste of Christmas in Mexico? Try this addicting Mexican Buñuelos recipe from Isabel Eats.

About National Hispanic Heritage Month

Each year, National Hispanic Heritage Month is observed from September 15 to October 15, to pay tribute to the generations of Hispanic Americans who have positively influenced and enriched the United States through achievements and contributions to society. This blog series celebrates the diverse and enriching heritages of Hispanic students, faculty and staff at Indiana University School of Medicine.