- Science is Not Boring! How to Talk About Science on Social Media, an in-person, best-practices workshop tailored for scientists and physicians | The June 5 event is presented in partnership with the Luddy School of Informatics, Computing and Engineering.

- “Improv(ing) Communication About Science and Health: How Theatre Can Help Experts Connect and Collaborate with the Community,” a Zoom presentation on May 31 | Longtin is the IUPUI Center for Translating Research into Practice (TRIP) Scholar of the Month for May.

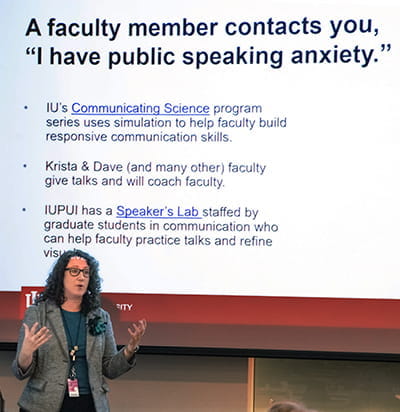

- Communicating Science 2025, the three-session workshop featured in this story | Apply by Nov. 30. Workshops take place once a month, January through March. Each cohort is limited to 16 participants. Apply early!

I sat across the table from a man I had met just moments earlier, and I began to rant.

For a full two minutes, I grumbled about how recent media and political emphasis on the high cost of college — and the absence of the emphasis on the value of higher education — has changed the trajectories of countless high school graduates. My kids’ futures now look vastly different than any of us had imagined, and I am not happy.

I understood the assignment.

The man across the table from me? His assignment was harder: Don’t engage right away. Let her rant. Then respond to her rant without saying anything negative. Look for shared values.

He replied with something close to: “I can see that you love your kids and want them to have a prosperous future. You really value education, and that’s admirable.”

Instantly, I could see that my “scene partner” empathized with me and understood my point of view. After working myself into a passionate rant just moments earlier, his eye contact, simple words and calm, encouraging demeanor changed the energy at the table. My heart rate slowed, and I could feel the tension in my chest deflate.

Improv for the win

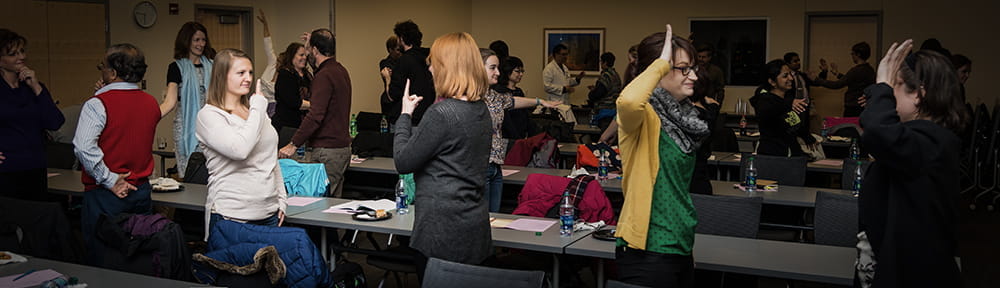

As I was ranting about negative media attention, a half-dozen or so other professionals from Indiana University School of Medicine were sitting across from colleagues, ranting about everything from ungrateful siblings to a spouse’s wild spending.We hadn’t gathered to gripe. We were simply knee-deep in an exercise rooted in the principles of improvisational theatre (improv, for short) that was designed to teach us to communicate more effectively. “The Rant” got us fired up for day two of the Communicating Science program, a three-session workshop offered by Faculty Affairs and Professional Development (FAPD).

Full disclosure: I am employed by FAPD. But I was genuinely moved by my experience as a Communicating Science program participant. As a seasoned communications professional with a degree in journalism and 25 years of experience under my belt, this communications exercise (and several others) taught me to look at communications in a completely new light — and it was powerful.

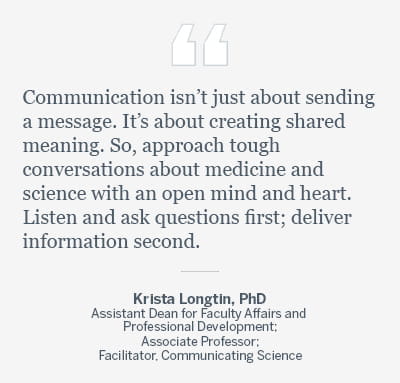

“The Communicating Science program to me is an opportunity for faculty members, learners and staff members to explore a new way of thinking about communicating, particularly communicating across disciplines and with the public,” said Krista Longtin, PhD, assistant dean for Faculty Affairs and Professional Development, associate professor in the departments of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Communication Studies at IU Indianapolis, and facilitator of the Communicating Science program.

“It offers strategies that are focused on really cutting-edge research in communication and provides faculty and other attendees with concrete tools that they can take back to their clinics or their labs to help them communicate more effectively with a variety of audiences.”

So, how does improv fit into the picture?

The work of researchers and practitioners in improv theatre “teaches us that there is much to be learned about ourselves and one another by leaning into, rather than resisting, the unknown,” Longtin explained in a post she wrote for the Public Library of Science (PLOS) Science Communication (SciComm) blog. She explains that applied improv takes principles, mindsets, tools and skills used by improvisational artists in theatre, comedy and music and applies those to experiences outside of artistic performances.

For IU School of Medicine faculty, trainees, learners and staff, these techniques can be especially helpful when we are placed in situations when communicating with patients, media, colleagues, presentation audiences, peers, neighbors, friends and others is important, necessary — and potentially difficult.

Take, for example, a physician’s encounter with parents who are hesitant to vaccinate their child. The physician knows the value of vaccinating children and wants to encourage the parents to reconsider. From the moment the physician walks into the exam room, the parents state their opposition and are adamant that they will not change their mind.

The physician, rather than responding by telling the parents they have been misinformed and are wrong to withhold vaccination, listens to the parents, then, as we learned in “The Rant” exercise, finds common values and responds with empathy. “I can see that you really love your child and are concerned about her long-term health. Can you tell me what makes you believe that this would be a bad or risky decision?” The parents can then explain their beliefs, and the physician can gently share the science behind why vaccines are a healthy choice.

Perhaps the parents respond that they have religious objections to being vaccinated. The physician can respond with something like, “I am also a person of faith, and I am so glad that the God I believe in gives us the tools we need to keep our children safe.”

“That shift from, ‘I’m just delivering scientific information to you’ to ‘I’m helping you to put this scientific information into the context of your identity and values,’ that’s a really important part of improv’s strategy for sharing information,” explained Longtin.

Bring a brick, not a cathedral

Empathy is a critical component of communicating science effectively. There are others, as well. Telling stories to make concepts clearer, approaching controversial or difficult subjects with curiosity and approaching everything with an open mind are others.

Empathy is a critical component of communicating science effectively. There are others, as well. Telling stories to make concepts clearer, approaching controversial or difficult subjects with curiosity and approaching everything with an open mind are others.

Improv artists have a saying that entails all three: “Bring a brick, not a cathedral.”

“Oftentimes when we approach difficult conversations, in particular, we approach them with a fully formed plan of how that conversation should go,” explained Longtin. “What would make you, as the speaker, feel most confident? How can you get your point across? What data do you need to be able to convince the other person of something?”

In other words, you have built your cathedral before you arrived at the conversation. The problem is, the other person in that conversation is usually coming with a prebuilt cathedral, as well.

“Improvisers say, if we’re building a scene together and I come with a fully formed script in my head of how this conversation will go, I’ll miss opportunities to build on your ideas,” says Longtin. “I’ll miss opportunities to connect with you and to be present with you in your realities and experiences. So, instead, the idea is, what if everyone comes with a pile of bricks, and together we build a cathedral? I build on your ideas. You build on my ideas. … The outcome of the conversation may be different than we anticipated, but it means that we both share in the outcome.”

When talking about science communication, Longtin says it’s important for scientists to appreciate the idea that those who are not experts in their own fields still come to the table with expertise. “They still come with a set of experiences that are valuable in that conversation,” she said. “And starting from asking a question — ‘What do you already know about this topic?’ — can really help that cathedral get built together.”

In the current climates surrounding politics and higher education, that’s a critical skill. “I think it’s easy for us as academics to get very ‘explainy’,” said Longtin. “And I think that, for me, the best conversations I have are the ones that I approach with the idea that I’m not sharing information, but I’m building something new with my audience.”

Communicating science is changing at IU School of Medicine

Longtin has devoted her career to researching ways to effectively communicate about science. And the IU School of Medicine is changing based on what she’s learned.

Longtin has devoted her career to researching ways to effectively communicate about science. And the IU School of Medicine is changing based on what she’s learned.

The Communicating Science program, started in 2016, has provided a practical experience for faculty, trainees, learners and staff to build and practice improv skills they can apply toward communicating their expertise. The program includes three, two-hour workshops (once a month in January, February and March) that cover topics like analyzing an audience, distilling the messages one wants to communicate and working with journalists. Applications are due each year by Nov. 30.

In addition, she and her colleagues, Jason Organ, PhD, associate professor of Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, and co-editor and writer for the PLOS SciComm blog mentioned earlier; and Mel Wininger, MA, teaching professor in English, worked with the Medical Student Education team in 2015 to change the approach used for assessing communication skills of medical students. The strategies used to evaluate and give feedback on objective structured clinical examinations (OSCEs) are now more holistic, focused on building relationships and not just making eye contact with patients, for example.

At the same time, the research communication course for biomedical PhD students moved away from being focused almost solely on the material part of communicating information (such as building effective PowerPoint slides and designing academic posters) and now includes theoretical components of building connections, empathy, credibility and trust.

“One of the ways that this work has made a difference is in the lives of our biomedical PhD students. Frequently, students come into the sciences because they have an interest in curing a disease, but also in advocating for science and the work that they’re doing,” said Longtin. “Prior to the work we have done with a communicating science minor program and revising the research communication course, there wasn’t a curricular place for students to explore that part of their professional identity.”

That has now changed. By approaching those courses with a focus on teaching fundamental behaviors associated with responsive communication, students learn to adapt their communication techniques based on their audiences — whether the audience at any particular moment is colleagues in the lab, policymakers or the general public.

Longtin says she now sees students finish the minor program or the research course who are more involved in advocacy work, in informing public policy. “They feel as if it is part of their job as scientists to be part of the national conversation,” says Longtin, “which I think is a really important part of colleges and universities in general — getting the great research we’re doing out to the general public to improve patient care and the lives of humans.

“So, for me, the way that we have changed people — changed lives — is by creating pathways for our students on the research track to see themselves as a fundamental part of sharing information with the public.”