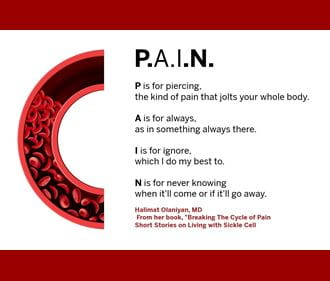

“At any moment, in a matter of seconds, I could have a sickle cell crisis,” writes Indiana University School of Medicine clinical pathology resident Halimat Olaniyan, MD, in her book, “Breaking the Cycle of Pain, Short Stories on Living with Sickle Cell.”

“As the crescent-shaped red blood cells coursing through my veins turn on me,” she continues, “they stick together and block the flow of blood in my body. It’s surprising the sheer amount of pain caused by the lack of oxygen to a joint.”

Olaniyan, who was diagnosed with sickle cell disease at age 7, said living with her illness can be very painful and debilitating.

“The pain comes in what people call sickle cell crises or vaso-occlusive events. You’re not getting blood flow to a certain part of your body,” said Olaniyan. “When you don’t have blood flowing properly, we call it a stroke. If it’s in your heart, we call it a heart attack. So, we can have that anywhere in our body.”

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, sickle cell disease, a red blood cell disorder that can cause harm to multiple organs when red blood vessels are blocked or break down, affects nearly 100,000 Americans. For those with the illness, the recurring pain often goes unnoticed by others unless shared with them.

“It can feel like a sharp jabbing or sometimes a jolt,” Olaniyan said. “People say it can feel like getting hit by a car, or for a football player getting tackled by 20 players.”

For some, it can be life-threatening and lead to heart conditions.

Ankit A. Desai, MD, a physician scientist with the Krannert Cardiovascular Research Center at IU School of Medicine, seeks to improve outcomes for patients with sickle cell disease who now have heart damage and are at risk of complications, including death. Desai, an associate professor of medicine at IU School of Medicine and a cardiologist at IU Health, is leading a $3 million grant received from the U.S. Department of Defense to evaluate the potential use of the inhibitor R-propranolol (R-prop), which is currently used as part of a mixture in propranolol, a beta blocker.

Ankit A. Desai, MD, a physician scientist with the Krannert Cardiovascular Research Center at IU School of Medicine, seeks to improve outcomes for patients with sickle cell disease who now have heart damage and are at risk of complications, including death. Desai, an associate professor of medicine at IU School of Medicine and a cardiologist at IU Health, is leading a $3 million grant received from the U.S. Department of Defense to evaluate the potential use of the inhibitor R-propranolol (R-prop), which is currently used as part of a mixture in propranolol, a beta blocker.

Propranolol is routinely used to treat heart problems, hemangioma, migraines and anxiety. Evaluating an existing therapeutic for other uses could help accelerate accessibility for patients more quickly, which is paramount for those with sickle cell disease, for whom the median age of death is 43 years of age.

The only difference between propranolol and R-prop is that R-prop does not demonstrate as much beta blocker activity, alleviating blood pressure concerns and heart rate side effects.

Desai, a specialist in pulmonary hypertension and sickle cell disease, is collaborating with Bum-Rak Choi, PhD, associate professor of medicine at Rhode Island Hospital and Brown University. He will work closely with Choi on data related to the development of fatal arrhythmias in sickle cell disease, studying damage to the muscle and function of the heart.

Addressing arrhythmia to prevent complications

The grant, “Repurposing Propranolol to Treat Sickle Cell Cardiomyopathy and Ventricular Arrhythmias: Role of Nonadrenergic Signaling,” will be used to study heart injury impact as well as rhythm disturbance impact in preclinical models of sickle cell disease.

“I think the Department of Defense support is doing so much more than just funding basic science,” Desai said. “It’s funding a disease that is underrecognized, underrepresented and supporting a broader goal in closing health care gaps at the same time.”

Currently, little is known about the true prevalence of sickle cell cardiomyopathy. But, based on Desai’s prior work, a significant proportion of individuals living with sickle cell disease appear to have fibrosis or scarring in their hearts. More recent work from others in the field shows that fibrosis may be present in even young children with sickle cell disease.

Between 1979 and 2017, there were more than 25,000 sickle cell disease-related deaths reported among Black patients in the United States. While mortality rates declined in children, they increased among adults with the disease because of acute cardiac, pulmonary and cerebrovascular complications.

“Cardiomyopathy or heart injury can predispose patients to a fatal rhythm disturbance called ventricular tachycardia,” said Desai, who leads the Center’s Cardiopulmonary Research Program.

“We believe that inflammation plays a key role in both creating this injured heart and exacerbating it. We are deeply interested in translating this potential therapeutic to patients, developing a clinical trial and trying to understand the potential impact of R-propranolol, given that propranolol appears otherwise to be well tolerated in patients.”

Olaniyan is optimistic about Desai’s study.

“I was literally so thrilled and I reached out to him,” said Olaniyan, who wants to pursue blood banking and transfusion medicine as a career. “The potential use of this beta blocker is a very new approach, and it’s really exciting.”

She said there has been a lack of research in identifying different options for this significant patient population that includes a disproportionate number of patients from minoritized populations.

“In the past five years, a lot of effort has been placed into developing new medications or repurposing different medications for sickle cell, which is amazing, said Olaniyan. “Before 2017, we had maybe one drug — Hydroxyurea, which is a great drug, and it’s still a mainstay of treatment.”

Olaniyan said Desai’s study is not only looking at whether the beta blocker could slow down cardiomyopathy and fibrosis, but also if it would have the potential to reverse and create healthier blood vessels to improve blood flow to the heart.

“For sickle cell, that would mean preventing or slowing any heart problems, and potentially reducing ‘sickling.’ If you can improve overall blood flow in your entire body it could mean reducing a lot of secondary consequences,” she said.

Previous research conducted by Desai, and published in the journal Blood, shows that Interleukin-18, a proinflammatory cytokine with essential regulatory function in the immune response, contributes to the development of inflammation in the heart and damage to the heart muscle. They also found that when you inhibit IL-18, it seems to improve fibrosis. That led them to experiment whether ventricular tachycardia could go away by inhibiting IL-18 using IL-18 binding protein and reintroducing it.

Could a generation be saved using the beta blocker, R-Propranolol?

“We recognized IL-18 as a potential therapeutic for the abnormal rhythm disturbance in the heart and the damage that we see,” Desai said.

IL-18 binding protein is not FDA-approved for human use. So, researchers sought alternative therapies. Through the use of R-prop, they uncovered new, molecular pathways that led to the aggravation of the IL-18 pathway.

“We found that R-propranolol was able to reduce the effects of Interleukin 18 in these sickled hearts and was able to stop abnormal rhythms,” Desai said. “Our grant will enable us to study how the drug does that. If we can better understand how, then we may be able to quickly translate its use in patients.”

Researchers also plan to evaluate potential for toxicity before introducing R-prop in a clinical trial.

Despite the recent FDA approval of Vertex and Bluebird’s gene editing therapies for sickle cell disease, people who have lived with sickle cell disease are still suffering from cardiac complications and are at risk of death and need interventions. In fact, some of those advanced therapies may be far from reach for many patients given the estimated costs.

Krannert Cardiovascular Research Center Executive Director Rohan Dharmakumar, PhD, said in the absence of an effective therapy to address cardiomyopathy and tachycardia in sickle cell disease, we risk losing a generation of people prematurely.

“While new therapies are being explored, cleverly repurposed drugs that have already had human exposure with strong safety profile, such as R-propranolol, stand to make major headway in solving a long-standing health issue affecting the heart and cardiovascular system in the United States and abroad,” Dharmakumar said.