A woman goes to the emergency room because she’s experiencing abdominal pain. She’s nervous and terrified. She doesn’t want to be there but understands the importance of seeking out care when able. A doctor arrives at her bedside to ask some routine questions.

“Are you pregnant?”

“No.”

“Are you sure?”

“Yes.”

“Let’s do a pregnancy test to be certain.”

“But doctor, there’s no chance I could be pregnant. I’m gay.”

Too often, LGBTQ+ individuals are met with dismissive and at times probing questions when they go to the doctor— making an already vulnerable moment more difficult. These situations can make it hard for LGBTQ+ patients to express their health concerns to their primary care physicians. From having the courage to “come out” to educating their physician on terminology that is comfortable for them, it can be exhausting.

While all patients should feel empowered to advocate for their care, why do so many LGBTQ+ individuals experience doctor visits that leave them uncomfortable or unheard? Is there a way to change the dynamic between LGBTQ+ patient and their doctor?Addressing the divide

Dustin Nowaskie, MD is a second year resident in the Department of Psychiatry at Indiana University School of Medicine. As a medical student, Nowaskie noticed a connection between the uncomfortable/ awkward doctor visits LGBTQ+ individuals experience and the lack of LGBTQ+-specific education during medical student training. In fact, last year Nowaskie co-authored a paper focusing on primary care providers’ attitudes when treating LGBTQ+ individuals.“Cultural competency in LGBT health care is a direct product of LGBT-specific education and a key component in providing quality care and building trust within the LGBT patient population,” Nowaskie wrote in the paper.

LGBTQ+-focused research is a rarity in the United States, with a previous estimate of only .1 percent of medical research focusing on LGBTQ+ issues1. Research among transgender-specific populations is also scarce, with only 0.008 percent of medical publications focusing on this area of medicine2.

LGBTQ+-focused research is a rarity in the United States, with a previous estimate of only .1 percent of medical research focusing on LGBTQ+ issues1. Research among transgender-specific populations is also scarce, with only 0.008 percent of medical publications focusing on this area of medicine2.

Nowaskie’s paper opens the door to alter that percentage. In his research, Nowaskie compared the cultural competency of LGBTQ+ health care issues among 127 Indianapolis-based doctors. His study revealed that while primary care physicians predominately agree that LGBTQ+ individuals need personalized care, over 70 percent of physicians did not feel well-informed on LGBTQ+-specific health needs, clinical management of LGBTQ+ care or on referring patients. Physicians also expressed a general lack of provider knowledge in regard to LGBTQ+ health, with an overall accuracy on knowledge questions as low as 51 percent.

“Imagine going to a doctor for breast cancer and learning that your physician only comprehends 51 percent of breast cancer issues,” Nowaskie said. “It wouldn’t be acceptable, and LGBTQ+ patients shouldn’t accept it either.”

Nowaskie’s paper concluded that there is a need for LGBTQ+-specific education and training. While the Association of American Medical Colleges, the Joint Commission and the American College of Physicians have called for additional culturally competent care to LGBTQ+ patients, not much progress has been made over the last 20 years. In the early 1990s, medical schools provided an average of 3.5 hours of LGBTQ+-specific education throughout four years of medical student training. Today, most medical schools still only provide between three to five hours of dedicated LGBTQ+ education, of which most time is dedicated to hard facts and statistics.

Strides in Indiana

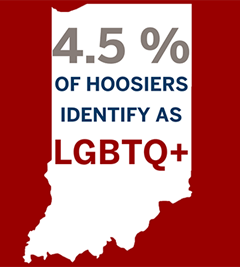

The LGBTQ+ Center at IUPUI compiled stats from a 2018 Gallup poll and the Williams Institute, which cited that approximately 4.5 percent of Hoosier residents identify as LGBTQ+— roughly 300,000 people. With a growing LGBTQ+ population, Nowaskie saw an opportunity to put his research and medical training experience to action.

The LGBTQ+ Center at IUPUI compiled stats from a 2018 Gallup poll and the Williams Institute, which cited that approximately 4.5 percent of Hoosier residents identify as LGBTQ+— roughly 300,000 people. With a growing LGBTQ+ population, Nowaskie saw an opportunity to put his research and medical training experience to action.

As a medical student, Nowaskie created a database called OutCare, where individuals could find primary care providers in Indiana who are equipped to support the LGBTQ+ community with their health needs. Nowaskie began speaking at conferences, sharing the database and its efforts to provide health care education and information to the LGBTQ+ community in Indiana. It didn’t take long for experts across the country to want to get involved, enabling a pathway for OutCare to become a national organization representing all 50 states, over 40 specialties and more than 1,800 health care providers.

“For OutCare, we wanted community members to tell their doctors that ‘You need this education,’” Nowaskie said. “In the few years since OutCare began, we’re already seeing a change.”

Nowaskie and other leaders at IU School of Medicine and IUPUI are working to increase the amount of LGBTQ+-specific education and training, enabling more physicians to feel competent and excited when providing care to LGBTQ+ patients.

As of 2019, the school provides 5.5 hours of LGBTQ+-specific education in the first semester alone with additional LGBTQ+ content found dispersed across the medical school curriculum, including opportunities for electives, clerkships, experience working at the Transgender Clinic at Eskenazi Health and attending the school’s annual LGBTQ Health Care Conference that occurs each spring.

As Nowaskie reiterated in his paper, research on primary care providers’ attitudes when treating LGBTQ+ patients should be conducted on a national level across all health specialties to better convey and address the health disparities of the LGBTQ+ community.

“The academic medical community is in an ideal position to improve attitudes and knowledge about LGBTQ care,” Nowaskie wrote.

From increasing LGBTQ+-specific education to funding research that reflects a community often left in the margins, medical schools and health institutions have an opportunity to enable change. These changes could create a foundation that integrates LGBTQ+ within all areas of health care.

In the first In the Margins story, health care disparities around the LGBTQ+ community were brought to light, starting with breast cancer. Unfortunately, lesbian, gay, transgender/non-binary and queer+ individuals face countless challenges in seeking information and treatment for their health. From the lack of representation in data to non-inclusive language—the disparities in health care for LGBTQ+ individuals is evident, but so are the opportunities for research institutions and medical schools to do more.

“There are going to be LGBTQ+ patients no matter what, regardless of specialty or location,” Nowaskie said. “This is a universal issue.”

1Boehmer U: Twenty years of public health research: inclusion of lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender populations. Am J Public Health 2002;92:1125-1130.

2Ortiz-Martinez Y, Rios-Gonzalez CM: Need for more research on and health interventions for transgender people. Sex Health 2017. doi: 10.1071/SH16148.