Keep the holiday season merry with toy safety tips from a pediatrician

IU School of Medicine's Alyssa Swick shares some of the most common toy-related injuries or safety issues during the holiday season.

Young patient, family travel from North Carolina to help advance Type 1 diabetes treatment

Heath Davis, 11, from North Carolina, is participating in an IU School of Medicine clinical trial testing whether an oral pill can preserve insulin production in people with Type 1 diabetes.

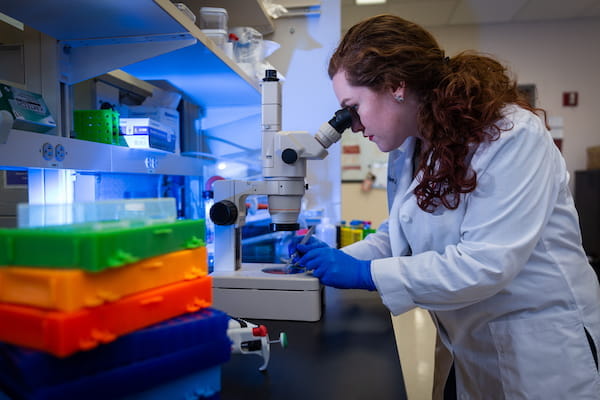

Specimen specialists: Medical laboratory scientists work behind-the-scenes to help determine cause of disease

IU School of Medicine is training more medical laboratory scientists — essential members of the healthcare team who work at hospitals, diagnostics labs and research laboratories throughout Indiana and beyond.

POPULAR TOPICS

Research and Discovery

The latest, most compelling research and breakthroughs led by our scientists and trainees.

Spirit of Medicine

The people behind our work to transform health care through quality, innovation and education.

Strategic Voices

Insight straight from IU School of Medicine leaders.

Student Life

An inside look at the school's innovative curriculum, robust support services, and rich student life.

Global Health

Improving health worldwide — and locally — while training globally minded physicians.

Indiana Health

Our work to make Indiana one of the nation's healthiest states.

POPULAR AUTHORS

Laura Gates

Senior Writer

Office of Strategic Communications

Jackie Maupin

Communications Generalist

Herman B Wells Center for Pediatric Research