Humor Break: Could there be a psychological pull toward a name-matching career in medicine?

Who wouldn’t want to see a physician named Dr. Healy? Or a cardiologist named Hart? It must be calming to visit with Dr. Stilwell. And what child could be afraid of seeing Dr. Parent or Dr. Huggins?

“As a pediatric hospitalist, I often see families who are worried or under stress,” said Kathryn Huggins, DO, assistant professor of clinical pediatrics at Indiana University School of Medicine. When families hear her name, she said, it helps to foster trust.

Learners and colleagues in the Department of Medicine benefit from the “sharp” skills and advice of Medical Education Specialist Sacha Sharp, PhD, MA. Her keen insights also serve the entire IU School of Medicine community as she helps to create a diverse learning and working environment in her role as chair of the school’s Diversity Council. Other Dr. Sharps (or Sharpes) work in family medicine, molecular genetics and emergency medicine.

Among the school’s esteemed researchers, Jason Organ, PhD, has published over 40 teaching modules in human anatomy. His lab at IU School of Medicine studies “the relationship between bone and muscle mechanisms at the whole-organ level, and how tissue-level mechanisms influence whole-organ function.”

Also consider the work of renowned bone cell biologist Lynda Bonewald, PhD. Who could question Dr. Bonewald’s selection as founding director of the Indiana Center for Musculoskeletal Health?

It seems serendipitous that these IU School of Medicine faculty landed in such positions. Or could there be something else at play? In 2015, a British family of doctors with the last name Limb, including an orthopedic surgeon, published a “lighthearted” study on nominative determinism in hospital medicine, asking, “Can our surnames influence our choice of career, and even specialty?” They found that of 313,445 names in the General Medical Council register for the United Kingdom, the median frequency of names relevant to medicine was 1 in 149.

It seems serendipitous that these IU School of Medicine faculty landed in such positions. Or could there be something else at play? In 2015, a British family of doctors with the last name Limb, including an orthopedic surgeon, published a “lighthearted” study on nominative determinism in hospital medicine, asking, “Can our surnames influence our choice of career, and even specialty?” They found that of 313,445 names in the General Medical Council register for the United Kingdom, the median frequency of names relevant to medicine was 1 in 149.

That’s certainly not overwhelming. Yet, could there be a subliminal pull toward a name-matching career? Take, for instance, Lord Walter Russell Brain, who wrote the standard work on neurology in the early 1900s and was the longtime editor of the medical journal Brain. In a similar vein, Organ is the current editor-in-chief of Anatomical Sciences Education. One of his earliest scholarly submissions gained immediate attention, being authored by “Organ and Mussell” (his grad school friend and colleague Jay Mussell, PhD, of Louisiana State University School of Medicine).

Organ originally aimed to be an anthropologist: “I wanted to play in the dirt and dig up fossils.”

Perhaps his forebears were directing another path. His grandfather escaped from the Lodz ghetto in Poland right before it was liberated at the end of World War II. He stowed away on a cargo ship to Canada and changed his name from Chaim Organek to Hyman Organ.

“Given that my grandfather had two organ names, I think it was destiny,” Organ said of the pull toward anatomy.

“Given that my grandfather had two organ names, I think it was destiny,” Organ said of the pull toward anatomy.

Similar destiny must have been directing Bonewald’s path as her interest in bone biology developed congruently with her interest in a young man named Jack Bonewald. Lynda McAdoo met her future husband while they were both students at the University of Texas at Austin and took the Bonewald name at age 19 when they married. Mr. Bonewald became a Navy officer and educator.

As a graduate student, Lynda Bonewald studied immunology and microbiology before joining the faculty at UT. A mentor pulled her into bone cell research in 1986.

“As a young assistant professor, I went to my first meeting for the society for bone and mineral research and submitted my abstract — I was told the reviewers had a great time with my name,” Bonewald said. “In a way, that gave me some early recognition in the field.”

Bonewald would later hold several leadership positions with the American Society of Bone and Mineral Research, including president. Another notable name among the society’s investigators: Dr. Henry Bone III, who founded the Michigan Bone and Mineral Clinic. There’s also a former Indiana Center for Musculoskeletal Health researcher named Andrea Bonetto, now at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, who studies the effects of chemotherapy on muscles and bones.

Bonewald would later hold several leadership positions with the American Society of Bone and Mineral Research, including president. Another notable name among the society’s investigators: Dr. Henry Bone III, who founded the Michigan Bone and Mineral Clinic. There’s also a former Indiana Center for Musculoskeletal Health researcher named Andrea Bonetto, now at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, who studies the effects of chemotherapy on muscles and bones.

“In the bone field, being a ‘bonehead’ is a compliment,” noted Bonewald.

Known throughout the scientific world for pioneering the field of osteocyte biology (cells which play a pivotal role in the functional adaptation of bone), Bonewald was recruited to IU to launch the musculoskeletal center in 2016. One of her first hires for the new center was operations manager Kyle Bone.

“I randomly came across the post for the opening on LinkedIn — I knew nothing about academia, biomedical research or musculoskeletal health, but the job was what I was looking for,” said Bone, who previously spent 10 years in telecommunications sales. “My name definitely put a spotlight on my resume out of the stack of resumes they received.”

Bonewald insists she hired Bone not for his name but “because of his intellect, his moral standing, his goals in life and his capabilities.” Nevertheless, Bone said, his name initially “came up in every meeting.”

For a period, the center was searching for a deputy director, and whenever Bone and Bonewald were asked about the status, they joked that they hadn’t found any qualified candidates who “fit the established naming convention.”

For a period, the center was searching for a deputy director, and whenever Bone and Bonewald were asked about the status, they joked that they hadn’t found any qualified candidates who “fit the established naming convention.”

Bonewald will soon be retiring from her position as the center’s director but will continue her research. If someone with a “bone” name cannot be found as her replacement, Bonewald said a muscle-related name would do — perhaps even a Dr. Strong or Dr. Power.

As for Bone, he has moved to a new position within the school of medicine: business manager for the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery. It’s a medical specialty he has personally interfaced with frequently. It seems the Bone family has a greater-than-average propensity for broken bones. Bone recalls “eight or nine” fractures while his father has suffered about 15, including his femur.

“After working at the musculoskeletal center, I do wonder if it could be a genetic predisposition,” Bone said.

What’s cooking at the School of Medicine?

For all the faculty with fortuitous names, there are many others whose names would indicate a different path. Some could easily trade their lab coats for chef coats.

IU School of Medicine boasts seven Cooks (or Cookes) and nine Bakers. Perhaps the school could host a top-chef showdown between Dr. Gerald Kitchens (anesthesia) and Dr. Emily Kitchin (rheumatology). Their culinary assistants might include Dr. Angus, Dr. Rice, Dr. Chow, Dr. Basile, Dr. Choplin, Dr. Smoker and Dr. Lasagna-Reeves.

IU School of Medicine boasts seven Cooks (or Cookes) and nine Bakers. Perhaps the school could host a top-chef showdown between Dr. Gerald Kitchens (anesthesia) and Dr. Emily Kitchin (rheumatology). Their culinary assistants might include Dr. Angus, Dr. Rice, Dr. Chow, Dr. Basile, Dr. Choplin, Dr. Smoker and Dr. Lasagna-Reeves.

While culinary medicine is an emerging field, that’s not what any of these faculty do. Among them are primary care physicians, oncologists, radiologists, psychiatrists, physiologists and researchers of various diseases like Alzheimer’s, kidney disease and pediatric cancers.

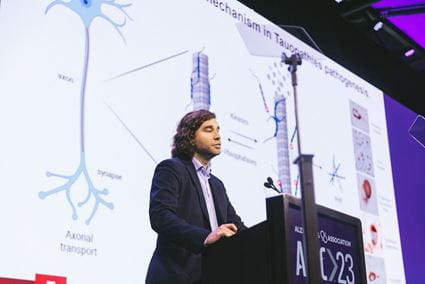

“When I was a kid, I used to help my mom sometimes in the kitchen — but only because I liked mixing things, like doing an experiment,” said Cristian Lasagna-Reeves, PhD, who recently was recognized by the Alzheimer’s Association for producing the most impactful study published in Alzheimer's research over the past two years.

Does he like lasagna? You bet! “My mom’s lasagna is the best dish in the world!”

Although Lasagna-Reeves grew up in Chile, his surname is Italian; his great-grandfather immigrated from Genoa, Italy. Years later, the family opened a bakery in Rancagua, Chile, called — you guessed it — Lasagna. Despite his culinary heritage, Lasagna-Reeves might not be a great pick for the IU School of Medicine culinary team; his wife rates his skills in the kitchen a “solid 2” on a 10-point scale.

Although Lasagna-Reeves grew up in Chile, his surname is Italian; his great-grandfather immigrated from Genoa, Italy. Years later, the family opened a bakery in Rancagua, Chile, called — you guessed it — Lasagna. Despite his culinary heritage, Lasagna-Reeves might not be a great pick for the IU School of Medicine culinary team; his wife rates his skills in the kitchen a “solid 2” on a 10-point scale.

Steve Angus, PhD, wouldn’t be much help, either. A researcher in rare pediatric cancers, Angus rates his culinary abilities a “3.” With a master’s in zoology, Angus might be better fitted for a herd of faculty with animal names, along with Department of Pediatrics colleague Marilyn Bull, MD, a renowned expert in child passenger safety. Bull, however, does offer notable skills in the kitchen. She grew up on a cherry farm and sold her first cherry pie in 1961 for 95 cents.

‘Pet Names’

Wolfes and Lions and (Panda) Bears — oh my! The pediatrics department could create a small zoo based on the furry last names of its faculty.

“I think children are naturally drawn toward animals,” said Joe Wolf, MD, a third-year resident in pediatrics. “My name does come in handy occasionally when I will let out a howl to get a patient to crack a smile.”

“I think children are naturally drawn toward animals,” said Joe Wolf, MD, a third-year resident in pediatrics. “My name does come in handy occasionally when I will let out a howl to get a patient to crack a smile.”

Robert “Bobby” Doggette, MD, once thought of being a veterinarian, but he doesn’t believe his name influenced his eventual career in emergency medicine. Interestingly, dogs are Dr. Dogette’s favorite animal — he has two Labrador retrievers that he trains for competitions and hunting.

In different paddocks and forests throughout the school of medicine, you’ll find Dr. Lamb, Dr. Buck, Dr. Coons, Dr. Fisch, Dr. Sparrow and a whole pack of Foxes.

“Just for the record, I used to work in a clinic with a Dr. Lamb and Dr. Hogg and took care of patients named Wolf and Squirrel,” noted Mark Fox, MD, PhD, MPH, associate dean and director of IU School of Medicine—South Bend and a professor of medicine and pediatrics. “One of my patients painted a picture for me of a very distinguished looking Fox in a lab coat with a stethoscope, which I cherish.”

While Fox spent a summer shadowing a veterinarian at the Tulsa Zoo, Bruce Lamb, PhD, executive director of the Stark Neurosciences Research Institute, spent one summer on a small Greek island near Crete studying the ancestor of the modern-day domesticated goat. These days, you’ll find him in the lab developing new animal models for Alzheimer’s disease as the principal investigator on one of IU School of Medicine’s top NIH-funded research programs, MODEL-AD.

Although his lab primarily works with mice, Lamb does have some farm animal associates. At conferences, he often shares a podium with Alison Goate, PhD, founding director of the Alzheimer’s research center at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. During the 2021 NIH Alzheimer’s Research Summit, Lamb and Goate were joined by speakers Barnes and Hay (Lisa Barnes, PhD, of Rush University, and Meredith Hay, PhD, of the University of Arizona).

Although his lab primarily works with mice, Lamb does have some farm animal associates. At conferences, he often shares a podium with Alison Goate, PhD, founding director of the Alzheimer’s research center at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai. During the 2021 NIH Alzheimer’s Research Summit, Lamb and Goate were joined by speakers Barnes and Hay (Lisa Barnes, PhD, of Rush University, and Meredith Hay, PhD, of the University of Arizona).

And then there was the time a reporter came to visit Lamb’s research laboratory.

“When I first started my lab in 1996, I set up a tissue culture room,” Lamb said. “We had a reporter visiting, and when he saw the room labeled ‘Lamb Tissue Culture’ he got very excited, as this was right around the time when Dolly the sheep was cloned. He was disappointed to learn that we weren’t cloning lambs.”

Hammers and Twiggs

Homer Twigg III, MD, doesn’t consider himself an extreme outdoor enthusiast, but he did collect many a twig to start campfires as a Boy Scout and a scout leader. Upon hearing his full name, Twigg said, people sometimes assume he’s a “hillbilly.”

“I do enjoy changing people’s preconceived notions about me,” said Twigg, whose lab investigates the lung microbiome and has established a large lung tissue biobank.

Twigg is among several faculty — including Woods, Fern and Waters — whose names might have nudged them down the path of forestry or environmental science.

Twigg is among several faculty — including Woods, Fern and Waters — whose names might have nudged them down the path of forestry or environmental science.

James Wood, MD, MSci, a pediatric infectious disease specialist, jokingly said he thinks of himself as “solid like an oak tree.” However, a more common association people make with his name is that of actor James Woods. The doctor’s name did come in handy during a recent patient interaction with a child having a rough day.

“She read my nametag, and I told her that I was actually made of wood — that made her laugh,” said Dr. Wood. “Her first name was Daisy, so then we talked about her being made of flowers.”

Then there are the doctors who could make a marvelous construction crew: Carpenters, Hammers and Sanders.

Kyle Carpenter, MD, MPH, specializes in robotic surgery, so the only time he uses saws or hammers is for his hobby of woodworking. Christopher Weaver, MD, has some carpentry skills from helping his dad and grandad build houses. In his job as an emergency physician, you might find him weaving sutures to close wounds.

Kyle Carpenter, MD, MPH, specializes in robotic surgery, so the only time he uses saws or hammers is for his hobby of woodworking. Christopher Weaver, MD, has some carpentry skills from helping his dad and grandad build houses. In his job as an emergency physician, you might find him weaving sutures to close wounds.

As a clinical neuropsychologist, Dustin Hammers, PhD, doesn’t use anything resembling carpentry tools, but when a patient does comment on his name, it tends to be positive: “I have been told many times that ‘Dr. Hammers’ sounds forceful, like I know what I’m doing.”

The only time he picks up a hammer is for the occasional home maintenance project. But could there be an esoteric connection between carpentry and psychology?

“Maslow’s hierarchy of needs suggests that safety and shelter security are basic required elements to psychological well-being,” Hammers said. “While I love to tinker around with home repair projects, my actually working on someone’s home would probably do more damage than good and, subsequently, lower their well-being. As a result, I am doing the most good by sticking to my day job.”