TO BEAT CANCER, we must understand every facet of its destructive path.

It begins long before patients are diagnosed by understanding whether genetics puts them at risk. Knowing this helps us devise ways to prevent cancer. Then, if a patient is diagnosed with cancer, we can flesh out the DNA profile of that person’s specific cancer—insights that help tailor effective therapy and lessen side effects. Once treatment ends, we have the tools to ensure a person’s disease is gone.

This is what it means to be comprehensive.

And it is how 287 researchers at Indiana University Melvin and Bren Simon Comprehensive Cancer Center carry out research that saves lives.

Laboratory research can take years to gain a granular understanding of disease at the cellular level. Some use those findings to identify targets and molecules that support the development of new therapies. And some translate to carrying out clinical trials that deliver cutting-edge care to patients.

Your support is vital in this work.

Your gifts empower IU School of Medicine to recruit top-flight scientists, provide them with stellar facilities, offer stable funding to pursue novel ideas, and launch exploratory trials. We’re grateful for your generosity and loyalty. Like us, you know research cures cancer.

Now, we’d like to share a few highlights of the progress we’re making—together.

BREAST CANCER

There are many types of breast cancer and numerous ways to describe them, but what if they share common roots?

Using sophisticated technology, Hari Nakshatri, PhD, identified four cell types that commonly give rise to breast cancer, upending longstanding assumptions about its origin. Today, that work is part of the Human Cell Atlas, allowing Nakshatri’s peers at IU’s Vera Bradley Foundation Center for Breast Cancer Research to disrupt the disease’s development. And it might enable us to pave a path toward tightly focused and non-invasive therapies.

Meanwhile, Jaeyeon Kim, PhD, and Olga Kim, PhD, discovered how progesterone influences the onset of triple negative breast cancer in women with the BRCA1 gene. Tarah Ballinger, MD, used the finding as a launch point for a clinical study where women with the mutation take a hormone blocker before undergoing a mastectomy. Next, tissue samples taken before and after the procedure are analyzed to see whether the drug thwarts cancer’s emergence.

Our researchers are also continuing their urgent search for solutions to halt triple negative breast cancer, a lethal form of the disease that isn’t responsive to established treatment protocols.

Kathy Miller, MD, continues to oversee a national phase II study of a drug pointed at those tumors. It aims at a target perched on the surface of cancer cells, delivering a direct strike against the disease. If successful, the trial, which includes estrogen-sensitive tumors, would expand internationally for phase III.

Miller and Ken Nephew, PhD, also lead a clinical trial testing a drug combination targeting a tumor’s genetic driver and a gene that helps cancer slough off therapy. It’s funded by a prestigious National Cancer Institute program grant worth $12.5 million and brings together 20 researchers from six institutions.

Our researchers also know that every patient’s response to therapy is distinct and impacts their quality of life. For example, Bryan Schneider, MD, showed that Black women are more likely to experience nerve damage while undergoing chemotherapy. So, he designed a clinical trial to confirm the genetic risk for neuropathy and determine the proper dosage that fights cancer—and prevents unnecessary pain.

LUNG CANCER

Our team of 10 researchers has made steady progress toward making immunotherapy a standard part of treatment regimens for advanced forms of lung cancer. Yet the team also knows there is so much left to do to halt one of the nation’s leading causes of cancer deaths.

Your gifts have been an integral component of our ability to make progress.

Philanthropic support proved essential in recruiting a trio of researchers to enhance our expertise. Trained by one of the most respected scientists in the field, Misty Shields, MD, PhD, brings vital knowledge in translational research for small-cell lung cancer. Rohan Maniar, MD, PharmD, will bolster our work in early drug development and phase I trials. And Julian Marin Acevedo, MD, will oversee our efforts to expand access and diversify patients who take part in cutting-edge trials.

At IU, we’ve shown it's possible to streamline therapy for patients with advanced forms of the disease, but now we’re striving to identify drug combinations that can be finely tuned for each patient.

A potential solution exists in a vaccine that might boost the effect of immunotherapy in patients fighting non-small cell disease. Last year, IU became one of a few sites in the U.S. for a collaborative clinical trial between American and Cuban researchers.

Our lung cancer program has also shown that circulating tumor DNA, faint remnants of cancer drifting in the bloodstream, is a helpful biomarker. We can use it to confirm that cancer has been eradicated and, just as important, take readings that help modify a patient’s treatment plan.

Nasser Hanna, MD, and Greg Durm, MD, are focused on whether immunotherapy can make a noticeable impact on the care of patients with early-stage lung cancer. Hanna leads a study among patients with stage I cancer, while Durm explores its utility among those with stage II and stage III disease.

Our patients also make lasting contributions to our work. Often, it’s difficult to obtain tissue samples of aggressive small-cell tumors, where cells multiply and evolve quickly. There’s a solution, albeit grim: take a biopsy after a patient passes away.

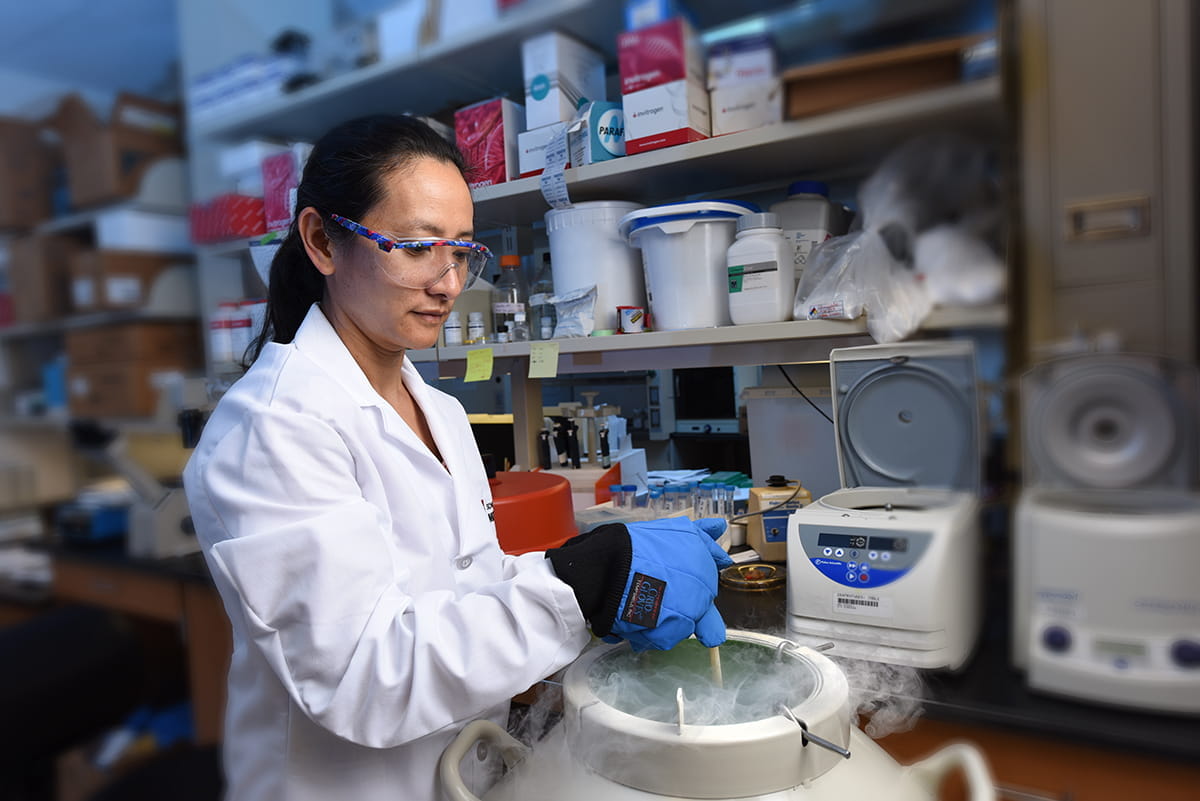

Many patients appreciate the difference it may make for future patients and consent to donate a sample shortly after their death. That tissue is stored in a biorepository overseen by Shadia Jalal, MD. This collection of tumor samples is an invaluable tool for researchers to use in cell and animal models that tell us how cancer operates and what drugs might stop it.

TESTIS CANCER

Each year, almost 8,000 men are diagnosed with testicular cancer. Each of them receives a chemotherapy regimen developed by Larry Einhorn, MD, whose discoveries moved the cure rate for the disease from 5 percent to almost 95 percent.

Impressive as that is, Einhorn and his colleagues still think there’s room for improvement.

There remains a subset of patients whose disease withstands treatment, and the cure for the disease can also exact a lasting toll on some men. Finding a biomarker to detect slight traces of the disease in patients who have completed initial treatment would be incredibly useful. Identifying solutions for all these issues animates our work.

Lois Travis, MD, SCD, continues to lead the Platinum Study, an international consortium trying to predict which patients are most susceptible to side effects from the drug cisplatin. The group demonstrated hearing loss in some patients is tied to the total dose they received during treatment. Others have a genetic variant that makes them more likely to experience painful nerve damage. These insights help oncologists better manage care for testis cancer patients and many more. Given that cisplatin is a drug used to treat nearly a dozen types of cancer, these discoveries can impact up to 6 million people treated worldwide each year.

Einhorn’s protégé, Nabil Adra, MD, focuses on men whose testis cancer is resistant to standard treatment. One of the new approaches he’s explored involves giving patients an oral form of immunotherapy for three months after undergoing high-dose chemotherapy. The clinical trial has shown early promise–and has been funded entirely by philanthropy.

Unfortunately, there is a small subset of men who do not respond to standard or high-dose treatments. Genomic testing among this group has revealed a specific protein spurs their cancer onward. Adra is searching for a way to block it. He is currently leading a clinical trial using an existing drug–and so far, the preliminary data is promising.

PANCREATIC CANCER

Halting pancreatic cancer demands a team approach—the kind we use at IU Simon Comprehensive Cancer Center.

In recent years, more than 20 faculty members—surgeons, oncologists, lab scientists, and biostatisticians—came together to improve a pancreatic cancer survival rate stuck at 10 percent. Together, they created nuanced disease models, identified new targets, and explored potential drugs.

In October 2022, they applied for a prestigious grant from the National Institutes of Health. If successful, IU will join just six institutions nationally with that distinction—proof it can move ideas from the lab to the bedside. Moreover, it would mark the cancer center as a national leader in pancreatic cancer research.

We’ve already made substantial progress. Melissa L. Fishel, PhD, created a state-of-the-art model that uses actual tissue to understand harsh conditions around tumors. Sometimes, that tissue comes from patients treated by IU Health surgeons, who handle the largest volume of cases in the country.

That model can also act as a proving ground for drugs like the one developed by Fishel and Mark Kelley, PhD, targeting a critical survival pathway for pancreatic cancer. Their molecule blocks a mechanism the disease uses to repair the damage inflicted by chemotherapy, and recently, the duo found that a modest dose also suppresses helper cells.

Now, they’re aiming to launch a clinical trial. Under that protocol, patients would receive the drugs for two weeks before surgery. Then, Fishel and Kelley would compare biopsies taken before and after this treatment to see whether the drug had an impact. Their goal: create a new and effective drug combination.

Our researchers know there are still other tools they can rely on to find answers for patients and improve care. Last year, IU added two faculty deeply versed in big data.

Jing Su, PHD, mines publicly available data in search of new targets and potential molecules to hit them—an efficient form of drug discovery. Ashiq Masood, MD, relies on bioinformatics to sequence cells from cancer tumors. Those penetrating analyses can tell us how cancer operates, discover vulnerabilities, and pave a way toward drug discovery.

And while there are questions about whether immunotherapy can work against pancreatic tumors, IU is tapping the expertise of a regional peer to see what’s possible.

Marina Pasca Di Magliano, PhD, a researcher at the University of Michigan, has identified cells that help cancer lock out the immune system–and the molecular pathways they use to do it. First, Magliano will target those pathways in cell models. Then, she’ll see how they translate in models developed at IU using samples provided by patients and stored in Indianapolis.

Picking this lock could help future therapies access tumors and destroy them.

Our Deepest Thanks

Every contribution to IU Simon Comprehensive Cancer Center makes a meaningful difference. But the support of Dean’s Council members offers an increased assurance of stability. Daring research takes time and reliable funding—the kind made possible by your generous contributions. Thank you for all you do to advance our important work to develop better treatment options for patients in Indiana and far beyond.