Living the IU School of Medicine core values every day

The jarring call came as Michael D. Davis, PhD, RRT, was out playing disc golf on an ordinary Tuesday afternoon in early June. On the phone was the Minister of Health for the Republic of Liberia. COVID-19 was hitting the West African nation hard, she said, and they needed his help.

“That was quite a phone call,” recalled Davis, assistant research professor of pediatrics at Indiana University School of Medicine. “It was exciting, flattering—terrifying.”

There was a flash of doubt in his mind about his qualifications to help lead Liberia’s pandemic response, but by that Sunday, he was on a plane to the land that has become his second home. Soon he was sitting around the “war room” table with government leaders and public health officials from the likes of the World Health Organization (WHO) and the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) in West Africa.

The story of why Liberia was calling on Davis—a registered respiratory therapist with a PhD in physiology and biophysics focusing on pulmonary medicine—begins about a decade earlier, in January 2011. That’s when Davis took his first trip to Liberia, invited by a colleague at the University of Virginia.

“I had no interest at all in medical missions,” he said. “It had never crossed my mind to do service work overseas.”

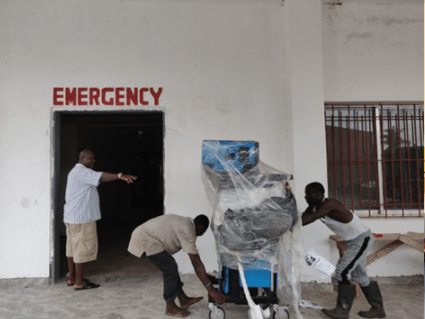

What he experienced in Liberia would forever change his perspective. In a country devastated by decades of civil war with an antiquated health care system, respiratory care was a virtually unknown concept. Although Davis did not have his PhD at that time, his skills as a respiratory therapist were valuable. The entire nation of Liberia had just one respiratory therapist at the national hospital in the capital city of Monrovia.

“It just seemed like I was more useful than ever,” Davis said. “Respiratory disease is a leading cause of death there—and that’s what I do!”

Training Africa’s first respiratory therapists

By fall 2011, Davis had put his PhD training on hold and all his personal possessions into storage for a temporary move to Liberia. On a subsequent trip in 2012, he teamed up with Liberia’s lone respiratory therapist, Joseph Moore, who had sought refuge in the United States during Liberia’s conflicts of the late 1980s. Moore had trained in America and eventually returned to his homeland, attempting to educate his Liberian colleagues on the value of respiratory care. Moore had a vision to start up a school to train more respiratory therapists, but as a busy clinician, he had no one to help structure the program and develop a curriculum. Davis’ arrival seemed a godsend.

Moore had a vision to start up a school to train more respiratory therapists, but as a busy clinician, he had no one to help structure the program and develop a curriculum. Davis’ arrival seemed a godsend.

While Davis questioned his own abilities to start a training program from scratch, he took on the challenge, reaching out to colleagues in the United States and contacts within professional organizations in his field. The Liberia Respiratory Care Institute (LRCI) opened in 2012—the first school of respiratory therapy on the entire continent of Africa.

“The work in Liberia involves a lot of partnerships,” Davis said. “Stateside, I got a lot of help from the National Board of Respiratory Care; they shared much of their curriculum with me, and we modeled our board exam after the one American respiratory therapists have to take, adding some questions specific to sub-Saharan Africa.”

LRCI’s charter class of respiratory therapists graduated in November 2015—the first in all of Africa. To date, the institute has trained 28 new respiratory therapists. Now the nation of Sierra Leone is looking to start up a training program modeled after Liberia’s success.

“If there were no trained respiratory therapists, COVID outcomes would have been much worse in Liberia,” Davis said.

Drastically reducing COVID-19 deaths

While Liberia managed to largely dodge the first global wave of the pandemic in 2020 due to aggressive shutdowns of its airport and borders, the nation was hit hard with the Delta variant in the summer of 2021. Davis had just returned from a trip to Liberia when the SOS call came from Liberian Minister of Health Wilhemina Jallah, a practicing obstetrician and gynecologist who has been a strong advocate of the respiratory institute and serves as its medical director. “It was really bad when I got there—it was the worst thing since Ebola,” recalled Davis, who had also helped Liberia through that global health crisis in 2014-15. “When I arrived that Sunday, the national COVID treatment unit, which we had helped the government set up a few months prior, was completely overrun with patients. If you were a patient who required treatment for COVID, the mortality rate was over 50 percent.”

“It was really bad when I got there—it was the worst thing since Ebola,” recalled Davis, who had also helped Liberia through that global health crisis in 2014-15. “When I arrived that Sunday, the national COVID treatment unit, which we had helped the government set up a few months prior, was completely overrun with patients. If you were a patient who required treatment for COVID, the mortality rate was over 50 percent.”

Davis immediately set to work surveying the current state of operations before developing a series of recommendations for improvement, which he presented to officials in the Liberian government and the U.S. Embassy, along with international public health officials from the CDC, WHO and the U.S. Agency for International Development. He also collaborated with the nonprofit Clinton Health Access Initiative, which redirected funds from another project to help train COVID unit workers in respiratory care.

“These reports made their way back to Washington. Congress was passing bills to provide funds for the pandemic in resource-poor areas in the world, and an extra $1 million was added for Liberia,” Davis said. “I’ve been working in public institutions my whole life, and I’ve never seen something move that quickly on the government level. Within a few weeks of changing strategies, COVID mortalities went down by half.”

Davis and his partners were able to train COVID unit workers and get oxygen resources where they were needed—even away from Monrovia out in the rural areas.

In a letter of appreciation, Minister of Health Jallah called Davis a “true humanitarian” and thanked him for his willingness to drop everything and serve as her trusted consultant during the COVID-19 surge, working alongside global partners to rapidly improve patient care and enhance Liberia’s health care infrastructure.

In a letter of appreciation, Minister of Health Jallah called Davis a “true humanitarian” and thanked him for his willingness to drop everything and serve as her trusted consultant during the COVID-19 surge, working alongside global partners to rapidly improve patient care and enhance Liberia’s health care infrastructure.

“While we hope the worst of the pandemic is behind us, we are better prepared than ever if it returns,” Jallah said.

Moses Massaquoi, director of the Clinton Access Initiative in Liberia, also commended Davis for his collaborative efforts to scale up access to oxygen and improve clinical skills of service providers.

“Your efforts have helped to guarantee the successful training of over 60 clinicians thus far, with reach across 12 major health centers and hospitals in COVID hot zones,” Massaquoi noted in a letter dated August 11, 2021.

Unsurprisingly, Davis’ contributions have earned high regard among his colleagues in the global respiratory care community. He was awarded the 2021 Toshihiko Koga, MD International Medal—the highest honor bestowed by the International Council for Respiratory Care (ICRC), given annually in recognition of the awardee’s excellence in promoting the globalization of quality respiratory care.

Leading collaborative efforts in the lab

Back at IU School of Medicine, Davis has been working on a different way to help reduce COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths. He was asked by longtime mentor and colleague Benjamin Gaston, MD, to take the lead on conducting lab experiments to determine if an asthma drug they had been developing could be used as a therapeutic for COVID-19, hypothesizing it would raise intracellular pH and kill the virus.

Back at IU School of Medicine, Davis has been working on a different way to help reduce COVID-19 hospitalizations and deaths. He was asked by longtime mentor and colleague Benjamin Gaston, MD, to take the lead on conducting lab experiments to determine if an asthma drug they had been developing could be used as a therapeutic for COVID-19, hypothesizing it would raise intracellular pH and kill the virus.

“Mike was the first person I spoke with, because it was his area of expertise and he had Ebola experience from West Africa,” said Gaston, vice chair for translational research at IU School of Medicine. “In every way, he was the perfect person to do that.”

Gaston and Davis are both clinician scientists at the Herman B Wells Center for Pediatric Research.

Davis collaborated with researchers in the Department of Microbiology and Immunology and was instrumental in convincing Dean Jay L. Hess, MD, PhD, MHSA, to commit funds to build a higher-capability laboratory for working with the SARS-COV-2 virus. The IU researchers have now proven their hypothesis and started up a company in an effort to secure investors and bring this potential COVID-19 treatment to market.

Gaston’s confidence in Davis stems from a 15-year relationship dating back to when Davis first started working in his lab at the University of Virginia. Not only is Gaston supportive of Davis’ frequent trips to Liberia, he indirectly may have inspired them by relating his own medical mission experiences to colleagues, first traveling to Liberia 40 years ago with David Van Reken, MD, professor of clinical pediatrics at IU School of Medicine.

The thing about Libera, Gaston said, is that dollars spent to improve health care go a lot further than they do in the United States.

The thing about Libera, Gaston said, is that dollars spent to improve health care go a lot further than they do in the United States.

“Resources are well spent in time, personnel and money in Liberia because of the impact you have on making people better—which is the whole reason we do what we do,” he said.

Gaston said Davis is extremely hard-working, committed to justice and excellent at cooperating with just about anyone to get things done.

“Everything he does is cooperative—he doesn’t carry an ego around,” Gaston said. “To me, it’s often amazing how well he makes things work. He’s just extremely gracious in guiding people to the right decisions.”

About this series:

Members of the Indiana University School of Medicine community strive to uphold and elevate the core values of excellence, respect, integrity, diversity and cooperation. This is the third in a series of stories featuring IU School of Medicine faculty, staff and students who exemplify these values.

Members of the Indiana University School of Medicine community strive to uphold and elevate the core values of excellence, respect, integrity, diversity and cooperation. This is the third in a series of stories featuring IU School of Medicine faculty, staff and students who exemplify these values.

Cooperation is manifested in collegial communication and collaboration. Medicine and science are team-based, and members of the IU School of Medicine community seek to foster an esprit de corps through their interactions with others, respecting the importance of all members’ contributions to the medical community’s shared goals. IU School of Medicine commends Michael Davis for demonstrating cooperation.